Place Attentive Training: A Model for Rural Counselor Preparation (JSC V20, Issue 1, Article 8)

Authors: Kirsten Murray, Jayne Downey, Anna Elliott, Rebecca Koltz

Abstract

Mental health disparities persist as a complex problem throughout the United States as rural communities face significant challenges accessing mental health services related to geographic isolation, scarcity, stigma, and financial cost. One contributing factor to this discrepancy is the shortage of, and challenge to retain, well-prepared mental health professionals. Rural schools are also less likely to be able to hire school counselors and mental health providers, further compounding access issues. This article presents a place-attentive counselor preparation model, implemented in rural Montana schools, designed to enhance the training and efficacy of clinical and school counselors entering the mental health workforce in rural settings, as well as increase sustainable mental health access for youth and families.

Keywords: rural, counselor training, community partnership, cultural humility

Place-Attentive Training: A Model for Rural Counselor Preparation

The consideration of place in rural counseling practice is a choiceto attune to the specific rural community’s needs, culture, resources, and barriers. Intentional training designed for rural counseling practice invites counselors-in-training (CITs) to consider how place has intersected with their own lives, and how to enter rural places with curiosity and a culturally humble commitment to both the people they serve and the place where they live. The Rural Mental Health Preparation Practice Pathway Partnership (RMHP4) Model provides an infrastructure to produce competent rural counselors and partner with high need rural schools and communities. Here, we introduce the model, guided by four distinct values, which informs four clear training steps, while also relying on four interacting systems for successful implementation. We reflect on lessons learned throughout our five years putting this model into practice, revealing complexities and the hidden but necessary ingredients that move the model from a check-list recipe into informed considerations for successful practice. Our intention with this article is to provide a contextual example highlighting how a place-attentive (White & Downey, 2021) curriculum can be designed and implemented. We hope that programs can use this model to adopt a place-attentive focus specific to their own programs.

Considerations of Place

Every counselor educator and counselor-in-training comes from some place, currently resides in a place, and many may find themselves in a new place at some point in the future. These places quietly surround and shape us, influencing how we see and understand ourselves, others, and our world. A recognition of the impact of place in our lives is important because “places make us: as occupants of particular places with particular attributes, our identity and our possibilities are shaped” (Gruenewald, 2003, p. 621). And yet, the importance of place has often been overlooked or taken for granted in counselor preparation programs. In fact, many programs have been unintentionally place-agnostic, with “little attention paid to preparing new counselors to work and thrive in a particular location” (Elliott, et al., 2024, p. 3). Roberts, et al. (2021) highlighted a disconnect for new professionals between their professional preparation and the knowledge and skills needed to thrive and remain in their new place and career.

The ever-increasing complexity of our world presents a growing need to recognize the power of place and the various ways that “place is an inescapable aspect of daily life and is intimately linked to our life experiences. Places provide the context in which we learn about ourselves and make sense of and connect to our natural and cultural surroundings; they shape our identities, our relationships with others, and our worldviews” (Butler & Sinclair, 2020, p. 64).

Given the importance that place has in shaping personal and community identity, history, and culture, as well as one’s day-to-day experiences and long-term opportunities, counselor preparation programs would do well to elevate the role of place and recognize its influence on people’s lived experience. CITs need opportunities to encounter and contextualize the various ways places shape their clients and themselves. Demarest (2015) suggests that carefully attending to place can help professionals such as teachers and counselors better understand and relate to students’ and clients’ life experiences and increase effectiveness in promoting health and well-being now and in the future. Meaningful experiences contextualized within a place can therefore be a key component of how one comes to understand oneself as well as the clients to be served. Place intertwines and interconnects our development with relationships, culture, history, economy, geography, land, and social systems of a location. These built environments offer a meaningful lens that help us understand and conceptualize our students and clients more fully, understanding both their interactions and their location in it (Butler & Sinclair, 2020).

Rural Places

Many different entities have attempted to define the rural places across our nation and those definitions tend to rely on the characteristics of 1) population density and 2) distance from an urban center. A recent scoping review found the federal government has 33 different definitions of rural places with many employed for the purpose of determining eligibility for specific types of funding (Childs et al., 2022).

One of the more commonly referenced definitions of rural places comes from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, 2022) which developed a locale classification system with a set of 12 metrocentric locale codes that define locales in relation to distance from urban areas; rural areas are described and defined as “fringe,” “distant,” and “remote” from the nearest urban cluster. This approach to defining rural places is perplexing because it defines rural by what it is not -- i.e., urban. This urban-centric definition can also be seen in the U.S. Census Bureau definition of rural as: “all population, housing, and territory not included within an urbanized area or urban cluster” (Ratcliffe et al., 2016).

However, ruralplaces are not monolithic, and they cannot be defined by geographical and population parameters alone. Rather, across the nation, rural communities and their schools demonstrate wide contextual variations in many important attributes such as geographic and professional distances, community size and amenities, salaries, technology access, health disparities, and poverty rates (Downey & Luebeck, 2023).

The state of Montana is the fourth largest state in the nation, spreading across 147,040 square miles of prairie, rivers, lakes, and mountains and is home to just over one million residents (7.59 people/sq mile) (USDHHS, 2023). As a state with vast distances and sparse population, Montana meets the typical parameters of rurality. However, Montana is not simply a setting for a movie or a scenic backdrop for its residents. Rather, the fabric of each rural community in Montana has a complex and dynamic culture shaped by unique social, economic, political, cultural, and historical elements.

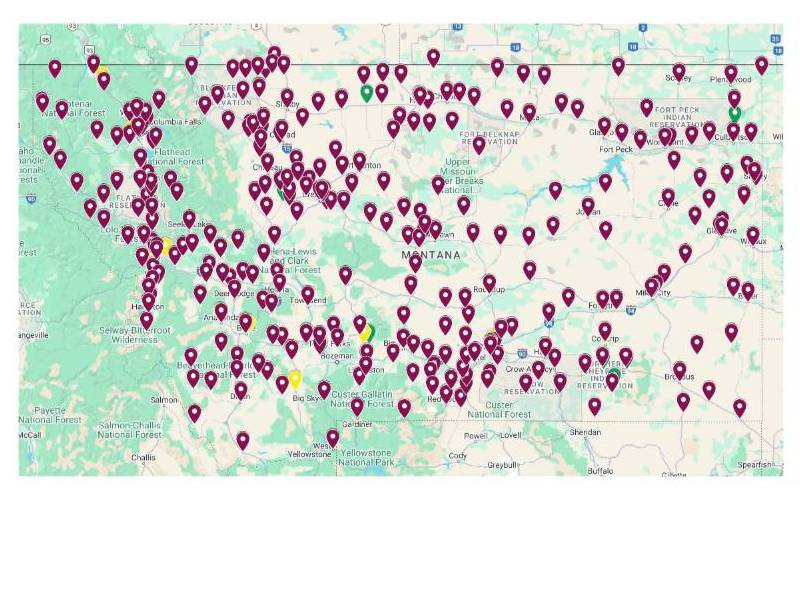

Figure 1 Map of Montana Eligible Rural Schools

Montana has 820 schools and nearly all of them are very small by national metrics. In fact, only 59 schools (7%) serve 500 or more students; more than half of the state’s schools have fewer than 100 students and over 60 are considered one room schools (OPI, 2024). The vast majority of school districts in Montana are classified as “small rural” (94.6%) and researchers have noted that no state has a higher percentage of small rural districts. Montana is only one of two states (Montana and North Dakota), where “85% of rural districts have fewer than 493 students” (Showalter, et al., 2023). Despite Montana’s rural context, counselor training programs historically offered little to no programming focusing explicitly on rural counselor preparation and placement. This fact became the impetus for a collective effort between Montana’s two leading universities to address rural counselor workforce development and to reduce rural health disparities through development of a place-attentive preparation program.

Place-Attentive Programming

Overview of RMHP4 Model

The RMHP4 Model aligns with the National Rural Health Association (NRHA, 2015) rural practice recommendations to improve retention of counselors in rural communities. Those recommendations include coupling financial incentives with training for rural specific competencies, noting that the financial incentive alone without the training is not enough for rural counselors to sustain long-term employment. Experts have clearly argued that the development of an effective mental health preparation program for rural contexts must address three factors that uniquely shape rural mental health professionals’ work: accessibility, availability, and acceptability (Downey, et al, 2021; NRHA, 2016; Siceloff, et al., 2017). In addition to these issues, we believe that an effective rural mental health preparation program considers a fourth factor – sustainability.

Given Montana’s massive geographic distances, accessibility to counseling services and/or a counselor preparation program is a serious challenge. In fact, Montana’s geographic distances are so vast, many communities meet the definition of not just rural but frontier. NRHA defined frontier as “sparsely populated areas that are geographically isolated from population centers and services” (NRHA, 2016, p. 1). Further, rural technology infrastructures are less reliable, making broadband connections for telehealth highly variable. The RMHP4 Model addresses issues of accessibility by strategically preparing and placing graduate counseling internship candidates in schools and communities where distance makes access to mental health services the most challenging.

The dearth of mental health providers working in rural areas highlights the lack of availabilityof services (NRHA, 2016). The lack of available rural mental health professionals is due in part to the fact that few training programs focus on preparing counselors for rural contexts and thus, little research has explored best practice recommendations for the preparation of counselors for rural schools and communities (Breen & Drew, 2012; Downey, et al, 2021; Hines, 2002; Morrissette, 2000; Saba, 1991). The RMHP4 Model addresses this issue by employing a cohort model in which graduate counseling candidates participate in a professional rural learning community throughout their program. In the rural context, acceptability refers to the stigma that can be associated with receiving mental health counseling. Hesitance to receive services is not uncommon due to lack of anonymity in rural communities (Breen & Drew, 2012; Downey et al., 2021). Through participation in RMHP4 Model counseling students become familiar with, and prepared to effectively respond to, reluctance to seek treatment.

Sustainability is a final factor addressed in the RMHP4 Model. By generating a pathway from field experience to rural professional life, counselors who engage in this process (Downey, et al., 2021). This cycle of professional preparation and sustainability is critical for successful rural mental health programs, as well as building a consistent networked community of individuals who have a passion for rural counseling.

In response to the considerable rural population in Montana, the authors developed a grant funded, place-attentive model of counselor preparation specifically designed to train graduate counseling students to persist in working effectively in rural Montana schools. The model, Rural Mental Health Preparation Practice Pathway Partnership (RMHP4), engages counseling students in a set of supervised, professional training experiences and coursework that prioritize efforts to enhance rural preparation, decrease isolation, and build a network of professional connections and support. Each year, 10 students are chosen to form a rural cohort and move through each phase of training together. The RMHP4 Model is represented by a compass diagram with three key components: values, systems, and training steps. Each component consists of four overarching values, four interconnected systems, and four specific training steps, all of which are integrated into the training process and relationships (see Figure 2). The four overarching values that inform the training are 1) Place-Attentiveness, 2) Cultural Humility, 3) Advocacy, and 4) Relationship. The four interacting systems that are essential partners in the training model are 1) the Rural School Systems, 2) the Rural Communities, 3) the University Systems, and 4) the Rural Mental Health Network.

Figure 2: RMHP4 Model Diagram

The RMHP4 values and systems are embedded within four sequential steps of the training model and consist of 1) the Rural Life Orientation, 2) the Rural Counseling Class, 3) the Rural Counseling Internship, and 4) Post Graduate Employment. Each of the above four steps involves the 10-person cohort (5 students from each University) engaging together in the training, with each step scaffolded to prepare students for the subsequent stage. The steps align with the National Rural Health Association (NRHA, 2015 ) recommendation for increasing emphasis on rural practice during training to improve retention of counselors in rural communities. Since the initiation of the model 48 out of 50 counseling students have completed the training, received their degree, and transitioned into professional practice. Each of the three components of the model is expanded upon below.

RMHP4 Values

The central values guiding the model are place-attentiveness, cultural humility, advocacy, and relationship. Our experiences over five years of implementation deepened our awareness and conviction of the importance of these values so that they were not only being taught but modeled by facilitators. Throughout, we aimed to be clear in the integration and significance of these principles.

Place-Attentiveness. Place-attentiveness (White & Downey, 2021) as a value is adapted from place-based learning and prioritizes counseling students’ attunement and respect for the specific geographical, cultural, and time bound context of the community and school system they enter (Gruenewald, 2003; Haarman & Green, 2023). We prepared students from the onset of their training to enter rural communities with consideration for how specific elements of the place (e.g. location, physical and financial access to resources, cultural beliefs) interact with the community, the school system, and approaches to mental health (Elliott et al., 2024). Place-attentiveness fosters a deeper understanding of the communal fabric that informs people’s presenting problems, patterns, and resources. When place-attentiveness is integrated into counseling practice it informs how we come to conceptualize and intervene with clients, while also considering how our own values and histories intersect with place.

Cultural Humility. Place-attentiveness aligns closely with the second RMHP4 value, cultural humility . Both emphasize attunement to context and honoring the unique and inherent perspectives of the people we serve. Within the last decade, cultural humility has been elevated in mental health fields as a critical response to address limitations of multicultural competence (Atkins & Lorelle, 2022; Lee & Haskins, 2021; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). Because multicultural competence has been criticized for suggesting a specific, achievable skill set, it falls short of acknowledging the inherent subjectivity and necessary continuation of accessing and deepening one’s culturally humble way of being (Hook et al., 2013). In contrast to multicultural competence, cultural humility is an intra- and interpersonal process that necessitates the ability to observe oneself as a cultural being, as well being curious and openness to another’s experience, with explicit emphasis placed on being accountable for how one’s experience and values affect the lens we see the world through (Hook & Watkins, 2015) . Cultural humility directly shapes how we enter a place.

Advocacy. Advocacy, the third value, is centered as both an action and a core value of the model that is informed by a place-attentive and culturally humble approach. In rural settings, advocacy has the power to be particularly transformative, especially where access to mental health resources tend to be lower (Grimes et al., 2014). By bridging our intentions and actions with advocacy, we aim to understand the mutually agreed upon needs of a community and collaborate to fulfill them. In the past, the internship placement process ran the risk of treating a rural internship as an extraction process; focusing on what a CIT or program needed to learn from a rural school. Instead, the RMHP4 model embraces advocacy by asking CITs to attend to the specific context of a rural community, enter from a stance of cultural humility and curiosity, and from there build collaborative relationships that facilitate the counselor and community working together to advocate for what is necessary for individual and community well-being.

Relationship. The fourth value of the model emphasizes the significance of relationship. We know that building relationships is paramount when fostering change for individuals, groups, families, and communities. This prioritization extends beyond the relationships built in the counselor/client relationship to the collaboration and connection between students, CITs, site supervisors, faculty, and school administrators. School systems are complex and the work of developing new functional field sites requires a high level of collaboration; prioritizing healthy relationships is essential for doing so successfully. Not only are healthy relationships among stakeholders beneficial for site development, but research focused on rural schools has found that relationship serves as both a protective factor and a continued motivating influence in school counselor and rural teacher retention (Azano et al., 2015; Boulden & Schimmel, 2022, Grimes et al., 2013; Grimes et al., 2018; Szumer & Arnold, 2023).

RMHP4 Interacting Systems

Rural School Systems. Not only are many Montana schools small, rural, and remote (Showalter, et al., 2023), but most of these rural schools are experiencing a shortage of school counselors. According to the most recent Montana’s Critical Quality Educator Report (2023), the number of unfilled counseling positions in our schools is thirteen times higher than in 2017 . This is a serious concern in Montana, as students are negatively impacted by the dearth of mental health resources and absence of necessary support. Considering our commitment to address Montana’s profound rural student mental health needs, we must also take into consideration factors of as geographical size and distance on in-person delivery programs and the availability of field placement resources, such as site supervisors and supports that counter isolation. The RMHP4 Model works to honor requests from schools who need services, yet the level of acuity, the impact of geographical isolation, and the potential scarcity of mental health resources and supervision may not be able to provide the support that CITs need for effective learning. Throughout implementation we have found it is critical that counseling students have strong supervision and support in the school to work with complex mental health needs, as well as access to adequate support for their professional development and well-being.

Rural Communities. When partnering with rural schools, it is critical to recognize that they serve as central hubs in their rural communities. Schools are the centers for collective community investment and connection. As such, each school partnership reflects an investment in understanding rural communities as a whole: stakeholders across businesses, clubs, law enforcement, healthcare, churches, local libraries, senior centers, and more. When entering rural communities, students seek to understand a places economic drivers, geography, historical contexts, and culture. When partnering with place, students are prepared to do so completely and build a deep understanding for the contexts of the students and families they serve. Students learn how to enter communities with humility and curiosity, learn from community members, and create partnerships that address gaps in resources and decrease isolation.

University Systems. Both Universities work to cultivate partnerships with rural schools and communities across Montana while also recruiting, selecting, and preparing counseling students for the intricacies of rural work. The RMHP4 Model utilizes a selective process to ensure counseling students are properly identified and assessed for inclusion in this experience. CITs from school, clinical mental health, and couple and family specialty areas are encouraged to apply.

To be considered for participation in the rural counseling cohort, counseling students complete an application process submitting a resume and letter of intent that addresses the following questions:

- What is your motivation to serve a rural community? On a scale of 1-10, rate your likelihood of relocating to a rural community for your internship and pursuing a rural position after graduation.

- What anticipated growth edges might you encounter when practicing in a rural community?

- What practices will you rely on to cultivate independence, combat isolation, and seek help? On a scale of 1-10 rate your tolerance for ambiguity, stress, and ability to respond with flexibility.

The RMHP4 leadership team then reviews applications, discusses the strengths and challenges of each application, and considers the needs of placement communities requesting an intern. Critically important to the team is that the students’ motivation is not solely based on financial benefits of participation (selected students receive a stipend to offset the expenses of engaging in rural internships); financial gain is not enough for counselors to persist in rural areas (NRHA, 2015).

Those who are selected to participate are placed in a rural school setting with an understanding of their respective roles by school administration. For example, if a clinical mental health CIT is in a school, they do not act as a school counseling intern, rather they act in the capacity of a school based mental health intern. Our inclusion of all CITs creates an opportunity to foster collaborative professional relationships, exposure to navigating the complexities of school systems across counseling specialties, and ultimately assists in extending mental health services to school staff and student families.

Rural Mental Health Network. Enveloping the RMHP4 Model is an emphasis on partnership. Isolation in rural counseling contexts is real, and the need for intentional and formal development of partnerships is critical to reduce counselor isolation and increase connection to other professionals (e.g., teachers, counselors, mental health professionals, 4-H leaders, University Extension agents, and educational leaders) across the state who share similar interests and goals related to youth rural mental health. During the implementation of the RMHP4 Model, we learned that there were many positive things related to youth mental health happening across Montana. We became aware of a missing mechanism to communicate, collaborate, and work together. As such, RMHP4 has begun to take initiative in the establishment of the Montana Network for Rural Youth Mental Health to build and increase rural partnerships that come together, stay together, and grow together. The Network will serve as a state-wide hub for education, opportunities, and support for counselors and mental health paraprofessionals working in rural schools and communities. We believe the Network will serve as a mechanism to promote the sustainability of the grant’s efforts through knowledge sharing and mobilization of key resources.

Four Steps in RMHP4 Training

Focusing on building professional relationships and networks envelops each step of the RMHP4 Model. Each step of the model is designed to be intentional and focused on a developmental progression of learning experiences. The four steps of the RMHP4 Model include: 1. Rural Life Orientation, 2. Rural Counseling Class, 3. Rural Internship, and 4. Rural Professional Practice.

Step 1: Rural Life Orientation. The RMHP4 model starts with an orientation to what rural life means in the context of counseling practice. This exploration begins with the Rural Life Orientation (RLO) where counseling students participate in a four-day experience where the cohort travels to a rural community, stays in the community, and meets with community stakeholders. Data collected to date reveals that the RLO experience achieves four outcomes for participants: 1) builds a more accurate and complex understanding of the rural experience, 2) raises awareness of strengths and assets of rural communities, 3) improves investment in rural counseling work, and 4) deepens a sense of cultural humility and inclusive practice (Elliott, et. al, 2024).

A priority of the RMHP4 Model is deepening students’ understanding of rural culture by entering communities with cultural humility. Through the RLO, counseling students are invited to understand the rural context and examine ways in which cultural components of place impact the counseling process. The RLO is a living, breathing experience that varies based on the community the cohort enters; no two experiences have been alike. However, implementing a practice of cultural humility remains a common thread across all experiences, and is a critical introduction to engaging not only one’s own values, but also the process of joining with rural communities and their people throughout the RLO.

Step 2: Rural Counseling Class. At the beginning of the cohort’s first internship semester, the RMHP4 model offers a Counseling in Rural Places course. The course is a weekend intensive structure oriented toward working as a counselor in Montana’s rural communities. The class is designed to prepare students for their internships by simultaneously building connections and strengthening community among participants from both universities. A primary project in the course is to simulate the RLO experience in their internship community. Here, students connect with community residents and stakeholders and begin to understand the histories, natural environments, economic and political factors, resources, strengths, and challenges that converge at this place. The course frames and gives language to rural challenges such as restricted access to quality mental health care, insufficient or lack of health coverage, mental health issues related to geographic isolation, the impact of poor infrastructure, factors of racism, colonization, and historical trauma, the effects of poverty and low educational attainment, cultural and social differences, stigma, and norms in rural communities. Strength based framings of communities are also introduced, including aspects of resources and resourcefulness, commitment, dedication, perseverance, creativity, generosity, trust, and investment in communal well-being. Beyond the content and curriculum, the course also provides an in-person experience for cohort members to reconnect, reducing the experience of isolation early in the internship experience.

Step 3: Rural Internship. Upon completion of practicum, RMHP4 CIT participants complete a rural school-based internship accruing the 600 hours necessary for their program of study. This is the crux of the RMHP4 implementation model, providing 10 rural communities with a total 6,000 hours of no-cost counseling services each year. The CIT participants are then able to apply their generalist counseling preparation while also scaffolding their learning of how unique rural contexts shape the practice of counseling. In addition to weekly supervision with site supervisors and their university group supervision, interns engage in monthly Montana Rural Counselor Network zoom sessions with the rural cohort, where they connect, share experiences, and engage in professional development with various rural life experts. The monthly zoom meetings are critical to reduce isolation often felt in rural communities and are in addition to their typical counselor education internship experiences.

Step 4: Rural Professional Practice.In the rural professional practice step, counseling graduates transition from their role as an intern to a professional in a rural community. Sometimes, interns continue in positions where they interned, though they often pursue open positions with other rural schools and community agencies with open positions. With grant funding, we have been able to offer graduates an additional stipend for this committed one-year experience . However, again beyond financial support, this post master’s experience presents as an opportunity for graduates to become more active in the rural network as colleagues with other professionals and mentors to incoming and future students. The graduates continue to develop relationships within the rural counseling network, as well as engage in post-graduate supervision. The RMHP4 Model invites postgraduates back to provide professional development during the monthly zoom meetings with current rural interns. This fourth step serves to expand our state-wide capacity to prepare rural school-based mental health services providers, increase the placement of these professionals in high-need rural schools and communities, reduce our shortage of rural school-based mental health service providers, and more fully meet the mental health needs of Montana’s rural students and community members.

Lessons Learned

Over the course of five years, the authors have engaged in continuous evaluation of the model and adjusted implementation. When facilitating place-attentive learning, three distinct lessons stand out: 1) Reflective Implementation; 2) Intentional Selection and Mindful Placement; 3) Building Student Community.

Reflective Implementation. When leading implementation, the authors aimed to demonstrate our own prioritization and capacity to embody cultural humility, place-attentiveness, advocacy, and relationship. Prioritizing our own awareness in relationship to these values has been an essential element of the training process. Engaging in feedback loops with one another, our participants, and community stakeholders has been especially helpful, and at times, challenging. We have worked to ask ourselves critical questions, such as: What assumptions are shaping our view of this community? How are we practicing cultural humility? How are we inviting each other into deeper curiosity about the contextual factors at play? How are we inviting and sustaining collaborative relationships with partners? Our positions in universities leave us especially vulnerable to systemic histories of mining communities for our own use while also risking an arrogance of expertise that ignores deeper understanding of community needs and practices (Christopher, et al., 2008). Thus, we have prioritized the need to hold awareness for how communities have experienced university intervention, and our work to maintain cultural humility, curiosity, and compassion has been paramount. We have been fortunate to partner with communities where there was mutual interest, collaboration, and investment. Last, we have had to be aware of our own capacity and support one another in establishing self-compassion and boundaries. Honest conversations about our capacity have led to joint reflections about where to establish boundaries (for example, when to intervene in a student’s relationship with their site and when to have them work out these negotiations), where we can delegate tasks (bring in a defined placement coordinator role to the model), and how to ebb and flow with one another’s’ capacity to accomplish tasks (for example, one team member takes responsibility to establish primary contact for the rural life orientation, and next year a different team member plans the orientation). These honest and intentional conversations could easily go unspoken and assumed. The relationship among the four of us has been central in establishing depth to this model so it goes beyond a simple implementation recipe or ‘to-do’ list.

Building relationships with communities has also been complex work. These complexities can vary from familiarizing sites with the demands of an internship, to setting boundaries around the levels of acuity our interns are prepared to treat, to negotiating the roles of a school counselor and mental health counselor in a school system. Throughout, our reflexivity has helped us have our house in order when it comes to recognizing our stuck points and assumptions.

Establishing and Sustaining Site Placements. Each year, the authors build a cohort of 10 students to engage in place-based learning and rural counseling service delivery. While the process of establishing relationships with sites and intentionally placing students requires the navigation of many logistics, site selection and placement requires thoughtful orientations to many complexities at play (Dean, et al, 2021). What follows is a description of four considerations for establishing and sustaining effective site placements: 1) intentional student selection and role induction, 2) mindful placement, 3) navigating professional variation, and 4) addressing developmental needs.

Intentional Student Selection and Role Induction. More students apply than we have capacity for, and attuning to specific dispositional qualities in our selection has proven helpful. Specifically, we ask students to self-evaluate their tolerance for ambiguity, stress, and ability to respond with flexibility, and have them explore how they plan to cultivate independence, contend with isolation, and seek help. Not only does writing to these qualities establish expectations for future experiences, but it also prompts students to begin to evaluate their stress and response patterns and attune to areas for growth. When evaluating applications, we are not looking for students to answer with veiled perfection but rather hold an honest self-assessment and a reasonable plan for action. This is essentially the beginning of our role induction process.

After the cohort is formed, mindful site placement of these students is orchestrated in a way that considers both their dispositional qualities and the variations of community partners to achieve effective and sustained service commitments. Matching students with sites has become very intentional work.

Mindful Placement. Appropriate site placements occur at the intersections of student preference, contacts from sites interested in program participation, geographical distance, and site supervisor preparation that meets our accreditation guidelines. Once these logistical details are matched, we consider what we know about the community and their resources, the school, the site supervisor, and the dispositional and development needs of the student to facilitate an effective match. For example, if we are aware that the student has identified establishing independence as a growth area, we would aim to match them with a supervisor who can scaffold the student from dependence to independence in a system that establishes clear role induction. At times, we are establishing new relationships with new sites. In these circumstances, we intentionally match students who can begin an internship with a high capacity for self-regulating through ambiguity, responding with flexibility, and establishing independence. These qualities have historically helped students effectively negotiate inconsistencies between what they have learned in the classroom and what they encounter in practice and engage in the crucial rural applied learning this program fosters. For example, students often encounter variations in how school counselors embrace their professional identity: from school counselors who primarily function as testing and 504 coordinators, to school counselors who continue to focus on a guidance model, and school counselors embracing the ASCA model, or school counselors who function primarily as individual counselors.

Navigating Professional Variation.After witnessing many professional role variations among our partnering sites, part of mindful placement has extended beyond ‘match’ and into supporting our students and partners at the crossroads of professional variation in rural contexts. When our interns enter these junctions with reflective tools to approach sites and supervisors with curiosity, cultural humility, and knowledge of how to effectively advocate, they encounter variations of practice with deeper understanding while developing clearer, more complex professional identities.

Addressing Developmental Needs. Our site partners are not only negotiating how to add supervision responsibilities to their already demanding workloads but are also encountering supervisees with variations of developmental needs and as they encounter some of their first opportunities to practice their future profession in a new rural context. Given these supervision and supervisee complexities, providing targeted supervision trainings and consultation among our dedicated supervisors have deepened their supervision practice and support network. When supervisors have access to supervision models that aid in supervisee conceptualization and purposeful supervision, they encounter supervisee needs with an informed framework to better guide supervisee growth and development. This has been particularly true when supervisors apply developmental supervision models to their circumstances and encounters with supervisees. In sum, there has been no year without demanding encounters. Initial efforts to align the values of the rural model with practice when selecting students, matching them with sites, and providing students and sites with helpful tools for learning have allowed for richer and more complex understanding of counseling in rural contexts.

Building Student Community. Prioritizing a sense of community among students has evolved over the five years of implementation. Initially, the ten students from two universities spent one, in-person gathering at the rural life orientation. Since then, we have prioritized in-person cohort contact at different intervals including the rural life orientation, the rural counseling class, traveling to present at a conference, and monthly zoom meetings. When the cohesion of the cohort is high, the group process has been bolstered by authentic disclosure, vulnerability, a sense of universality about rural work, and shared problem solving (Degeneffe, et al, 2021). This network of connection deepens the learning of all involved and has meant that we prioritize time and team building for these connections to flourish.

Throughout the training process, the authors have sought to navigate a continuous tension between content and process. Without necessary content, the cohort risks entering rural sites as if they are homogenous to any other context, and without necessary cohesion, the team risks encountering rural contexts in isolation. Learning to execute both needs continues to be a tension we hold, always wishing we had more time with students in our limited capacities. Learning to use our time wisely to foster effective group dynamics and deliver important content has relied largely on experiential activities and flexing our course schedules to allow time for students to share authentic disclosures and struggles. To foster cohesion, experiential learning, and shared problem solving, we have relied on the following activities: role plays and processing, photo projections and meaning making, insight-oriented games, and art expression activities. Throughout these activities, we aim to consistently scaffold in content about rural work from the reading into discussions and presentations. We find that effective use of our in-person time focuses on group process and cohesion building while our online meeting time lends itself to more encounters with content and guest speakers.

Call for Continued Work

Rural mental health disparities remain a pervasive problem. Though this model begins to address some of the mental health access barriers in rural Montana, and perhaps ongoing work is essential. First, our profession is responsible for recognizing and addressing populations and services we tend to overlook. We must consider where our graduates go on to practice, if their professional services are accessible, how they remain insulated from serving high need rural demographics, and what specific preparation and supports could assist them in addressing rural mental health disparities. Further, training programs must consider what students are we neglecting to recruit and retain, and how can we make counselor training more accessible to more people? In the context of rural preparation, creating a sustainable workforce by recruiting students already committed to practice in the rural places they are from remains a direct pathway to increase and sustain the workforce in rural areas. When we continue to recruit and retain students from our more populated epicenters, we are contributing to location bound ecosystems of counseling services that are insulated from our rural and high need populations. And, without specialized preparation of how to effectively practice in rural communities, we are failing our rurally place-committed students before they even begin. Professionally, we are responsible for continuing to attend to accessible education, and ultimately, accessible counseling services.

Our profession must also begin to consider the impacts of place on the counseling process and counseling relationship. When we work from a place-agnostic orientation, we run the risk of metro-centric thinking which can lead us to treating rural places “as-if” they were urban. Our rural students, schools, and communities deserve better. Conceptualizing and allowing place to inform our interventions not only leaves us more responsive to rural needs, but considers greater systemic impacts across all communities of practice . Gruenwald (2003) emphasizes factors of place consciousness that include political, ecological, economic, historical, perceptual, and cultural dimensions. Remaining conscious of how these dimensions intersect with presenting problems and patterns delivers more complex and rich understandings of clients’ lives to inform more tailored interventions that integrate systemic factors. As counselor educators we must consider what value-laden assumptions we bring into our training and supervision, and how we can stand to more effectively and ethically prepare counselors-in-training through place-attentive conceptualization and interventions. For example, understanding the elevated risk of suicide, the stigma of mental health issues, and the potential lack of exposure to what counseling consists of are all factors that will influence how and if rural community members will access mental health resources. Counselors having a nuanced understanding of those factors will allow them to tailor their outreach efforts and counseling approach.

Further, attending to dimensions of place positions counselors to more readily consider the impacts of social positioning and implications of power present in the interventions they are providing (hooks, 1990). Holding a rich understanding of dimensions of place can also reveal systemic strengths easily overlooked when adopting an individualistic vantage point. Connecting clients with responsive dimensions of their communities builds towards more sustaining change, and adopts place as a central component for security, belonging, meaning making, and self-expression (Saar & Palang, 2009).

Rural places and their people are at risk of continuing to be overlooked by the counseling

profession. Standard insular practices of recruiting, training, and providing services

within closed loops of urban/suburban epicenters is all too common. To break these

cycles and address rural health disparities, counselor educators can begin to integrate

considerations of place into our curricula, resist place agnostic practice, and model

the importance of place-attentive counseling. By integrating rural specific curriculum,

and models like RMHP4, counselor educators uniquely position themselves to build a

collaborative model of care and advocacy with rural schools and communities.

References

Atkins, K., & Lorelle, S. (2022). Cultural humility: Lessons learned through a counseling cultural immersion. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 15(1). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol15/iss1/9

Azano, A. P., & Stewart, T. T. (2015). Exploring place and practicing justice: Preparing pre-service teachers for success in rural schools. Journal of Research in Rural Education,

30(9), 1–12.

Boulden, R., & Schimmel, C. (2022). Factors that affect school counselor retention in rural settings: An exploratory study. The Rural Educator, 43(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.55533/2643-9662.1334

Breen, D. & Drew, D. (2012) Voices of rural counselors: Implications for counselor education and supervision, Counseling VISTAS (1). Retrieved from

https://www.counseling.org/resources/library/vistas/vistas12/article_28.pdf

Butler, A. & Sinclair, K. (2020). Place matters: A critical review of place inquiry and spatial methods in education research. Review of Research in Education, 44, 64–96.

Childs E. M., Boyas, J. F., & Blackburn J. R. (2022)Off the beaten path: A scoping review of how 'rural' is defined by the U.S. government for rural health promotion. Health Promot Perspect.12(1), 10-21.

Christopher, S., Watts, V., McCormick, A. K. H. G., & Young, S. (2008). Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American journal of public health, 98(8), 1398-1406.

Dean, B.A., Sykes, C. How Students Learn on Placement: Transitioning Placement Practices in Work-Integrated Learning. Vocations and Learning 14, 147–164 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-020-09257.

Degeneffe, C. E., Grenawalt, T. A., & Friefeld Kesselmayer, R. (2021). Relationship Building in Cohort-Based Instruction: Implications for Rehabilitation Counselor Pedagogy and Professional Development. Rehabilitation Research, Policy & Education, 35(1).

Demarest, A. B. (2015). Place-based curriculum design: Exceeding standards through local Ivestigations. New York: Routledge.

Downey, J., Elliott, A., Koltz, R., & Murray, K. (2021) Rural school-based mental health: Models of prevention, intervention, and preparation. In A.P. Azano, K. Eppley, & C. Biddle (Eds.) Handbook on Rural Education in the U.S. London: Bloomsbury.

Downey, J. & Luebeck, J. (in press). Professional learning for rural and remote teachers. In J. Johnson & H. Harmon (Eds). Handbook on rural and remote education. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Downey, J. & Luebeck, J. (2023). The power of three: Leveraging trilateral partnerships to support and sustain rural educators. In S. Hartman & B. Klein (Eds). The middle of somewhere: Rural education partnerships that promote innovation and change. Harvard University Press.

Elliott, A., Koltz, R., Murray, K., & Downey, J. (2024). Preparing for place: A case study of rural counselor training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12307

Grimes, L. E., Haskins, N. H., & Paisley, P. O. (2013). “So I went out there”: A phenomenological study on the experiences of rural school counselor social justice advocates. Professional School Counseling, 17(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.5330/PSC.n.2013-17.40

Grimes, L. E., Spencer, N., & Goldsmith Jones, S. (2014). Rural school counselors: Using the ACA advocacy competencies to meet student needs in the rural setting. VISTAS Online, 58, 1-10.

Grimes, L. E., Haskins, N., Paisley, P. O. (2018). So I went out there: A phenomenological study on the experiences of rural school counselor social justice advocates. Professional School Counseling, 17(1), 40 - 52.

Gruenewald, D. (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(4), 3–12. https:// doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032004003

Haarman, S., & Green, P. M. (2023). Does place actually matter? Searching for place-based pedagogy amongst impact and intentionality. Metropolitan Universities, 34(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.18060/27203

Hines, P. L. (2002). Transforming the rural school counselor. Theory into Practice, 41(3), 192 - 206.

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington Jr., E. L., & Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology 60(3). https://doi.org/0.1037/a0032595

Hook, J. N., & Watkins, C. E. (2015). Cultural humility: The cornerstone of positive contact with culturally different individuals and groups. American Psychologist, 70(7), 661–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038965

hooks, b. (1990). Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston: South End Press.

Lee, A. T., & Haskins, N. H. (2022). Toward a culturally humble practice: Critical consciousness as an antecedent. Journal of Counseling & Development, 100, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12403

Montana Critical Quality Educator Shortages (2023). Montana Office of Public Instruction. Retrieved from https://bpe.mt.gov/_docs/Critical-Quality-Educator--Report-Jan-2023.pdf

Morrissette, P. J. (2000). The experience of the rural school counselor. Professional School Counseling, 3(3), 197 – 208.

National Center for Educational Statistics [NCES] (2022). Locale definitions.

https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/annualreports/topical-studies/locale/definitions

National Rural Health Association Policy Brief (2015). The future of rural behavioral

health, retrieved from:

https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/NRHA/media/Emerge_NRHA/Advocacy/Policy% 20documents/The-Future-of-Rural-Behavioral-Health_Feb-2015.pdf

National Rural Health Association Policy Brief (2016). The Definition of Frontier. Retrieved from:https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/getattachment/Advocate/Policy-Documents/NRHAFrontierDefPolicyPaperFeb2016.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US

Office of Public Instruction [OPI] (2024). Facts about Montana Education. Retrieved from

https://opi.mt.gov/Portals/182/Ed%20Facts/2024%20Ed%20Facts%20FINAL.pdf?ver=2024-07-01-145207-587

Ratcliffe, M., Burd, C., Holder, K., & Fields, A. (2016). Defining Rural at the U.S. Census

Bureau, ACSGEO-1, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/acs/acsgeo-1.pdf

Roberts, P., Cosgrave, C., Gillespie, J., Malatzky, C., Hyde, S., Hu, W., Bailey, J., Yassine, T. &

Downes, N. (2021), ‘Re-placing’ professional practice. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 29, 2, p. 301-305.

Saba, R. G. (1991). The rural school counselor: Relations among rural sociology, counselor role, and counselor training. Counselor Education & Supervision, 30(4), 322 – 330.

Saar & Palang (2009). Dimensions of Place meanings. Living Reviews in Landscape Research, 3

(3), Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2236/a35cd5459060f1d769034548099ca3340f4d.pdf

Savage, A., Brune, S., Hovis, M., Spencer, S., Dinan, M., & Seekamp, E. (2018) Working together a guide to collaboration in rural revitalization, NC State Extension, Retrieved from https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/working-together-a-guide-to-collaboration-in-rural- revitalization#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIf%20you've%20seen%20one,%2C%20natural%20resources%2C%20and%20demographics.

Showalter, D., Hartman, S.L., Eppley, K., Johnson, J., & Klein, R. (2023). Why rural matters 2023: Centering equity and opportunity. National Rural Education Association.

Siceloff, E., Barnes-Young, C., Massey, C., Yell, M., & Weist, M. (2017). Building policy support for school mental health in rural areas. In K. Michael and J. Jameson

(Eds.) Handbook of Rural School Mental Health. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Szumer, R. T. O. & Arnold, M. (2023). The ethics of overlapping relationships in rural and remote healthcare. A narrative review. Bioethical Inquiry, 20, 181-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-023-10243-w.

Tervalon, M. & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in definition. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–126.

US Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (2023). Overview of the State of Montana. Retrieved from: https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/Narratives/Overview/fcfa2a07-1e29-4111-9d9c-1ae64527ee16#:~:text=As%20of%20July%202021%2C%20Montana's,Figure%20.

White, S. & Downey, J. (2021). International trends and patterns in innovation in rural education. In S. White & J. Downey (Eds.) Rural education across the world: Models of innovative practice and impact. Springer Nature Singapore.