Rural Communities' Perceptions of Gender and Sexuality Diverse (GSD) Youth's Needs: Ethnographic Reflection in Search of a Path Forward (JSC v20 article 6)

Authors: Ania Bartkowiak and Jeremy Shain

Correspondence regarding this article can be sent to anna.bartkowiak@montana.edu

Abstract

In rural areas, Gender and Sexuality Diverse (GSD) youth encounter distinct challenges. The level of support for GSD youth varies among rural communities. This study resulted from a collaboration between a researcher who conducted phenomenological and ethnographic research in a Montana rural community to offer insights into a culture and community perceptions of GSD youth’s needs and an experienced school counselor who specialized in establishing support systems for GSD youth in rural schools. The article reviews the findings from the ethnographic study, which is categorized into themes, and presents an action plan for school counselors working in rural communities.

Keywords: gender and sexuality diverse (GSD), school counseling, community assessment, rural community, rural schools

Rural Communities’ Perceptions of Gender and Sexuality Diverse (GSD) Youth’s Needs - Ethnographic Reflection in Search of a Path Forward.

The Trevor Project (2006) reported that GSD young people are more than four times

likely to attempt suicide and that a staggering 41% of young GSD people considered

attempting suicide (including about 50% of polled transgender and nonbinary youth).

CDC statistics regarding problematic youth behaviors documented that suicidality increased

by an unprecedented 62% from 2007 to 2021 (Desai & Affrunti, 2023). Likewise, statistical

information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System has long suggested that GSD youth are more likely than their cisgender

heterosexual counterparts to report depression and suicidal ideation (Kann, 2018).

This population is also at an increased risk of harm from unsafe sexual practices

and substance use than their peers (Kann, 2018). Studies have shown that youth in

rural areas generally exhibit more signs of distress and crisis compared to their

urban counterparts, but the findings regarding the differences in struggles between

rural and urban GSD (Gender and Sexual Diverse) youths are inconclusive (The Trevor

Project, 2006). The significance of studying GSD youth in rural areas lies not solely

in the indications of crisis but in the prevalence of their perceptions of how

they are regarded within their communities. A substantial 69% of rural GSD youth

reported feeling that their local areas are "somewhat or very unaccepting of LGBTQ

people," in contrast to only 19% of their peers in large cities, 26% in suburban areas,

and 44% in small cities or towns (The Trevor Project, 2006). Understanding the factors

that influence the experiences of GSD youth is crucial in identifying ways to enhance

their likelihood of receiving support within the limited spaces where they interact

with their communities, thereby improving their quality of life.

These statistics on GSD youth suicide and sense of community acceptance in rural areas tell a story about the alienation, helplessness, depression, and anxiety that children and adolescents experience (Baker, 2016). The challenges that the GSD young population faces every day in their hometowns are significant, from being a target of overt aggression such as bullying to the lack of support from adults in their small social circles (Baker, 2016). One defining aspect of rural settings is the limited in-person social exposure for children. The size and make-up of the youth population they interact with daily is often fixed, with changing schools or relocating being impractical, regardless of the hardships experienced in their environments. Obstacles to connection, such as the lack of public transportation and reliable access to mental health and counseling services, are common rural realities (Stewart et al., 2015).

This challenging landscape of rural America serves as the macro-context for GSD youth. It is crucial to consider the various aspects of the environment in which they live to help understand the GSD youths’ realities. Researchers (Gray et al., 2016) found that rural LGBTQ+ youth frequently encountered negative attitudes and discriminatory behaviors, often manifesting in verbal and physical harassment. While rural settings can provide support and a sense of belonging (De Pedro et al., 2018). The GSD youth experience varies widely across rural communities (Baker, 2016). The tight-knit nature of rural communities can increase stigma, as fewer individuals hold positive attitudes towards LGBTQ+ issues compared to urban areas (Oswald & Culton, 2003). Still, rural communities also have the potential to become a source of support and acceptance – especially for its GSD youth (Baker, 2016).

The school environment is one of the staples in each rural community, and it is

integral to examine a school’s policies to gain additional insight into the reality

of GSD youth. Research indicates that rural schools often lack comprehensive anti-bullying

policies, access to Gay-Straight Alliances, and inclusive LGBTQ+ curricula compared

to urban schools(Kosciw et al., 2015). Researchers (Adelman & Woods, 2006) noted that

schools “can be hostile places where heterosexism and homophobia…flourish” (p. 6).

Bullying based on perceived sexual orientation and gender non-conformity often begins

in elementary school and often increases as students move to middle school (Szprengiel,

2018). A GLSEN report (Kuff et al., 2019) notes that GSD students who live in rural

areas are more likely to experience homophobic and transphobic bullying in schools

than queer students who live in more urban areas.

Moreover, GSD students residing in rural areas have expressed receiving less support

from school staff than their urban and suburban counterparts (Kuff et al., 2019).

In certain parts of the USA, the situation has recently deteriorated. For instance,

officials in Florida have demonstrated a lack of support for GSD youth by making curriculum

updates and implementing biased school policies. This institutional lack of support

often results in LGBTQ+ youth feeling too apprehensive to openly express their identities,

which exacerbates their stress and feelings of isolation, contributing to mental health

challenges, substance abuse, and an increased risk of suicide. In some states, school

staff are even legally obligated to disclose a student's GSD identity to their parents

and caregivers (Movement Advancement Project, 2024).

One of the support links for the GSD youth is held in the role of a school counselor.

With a Montana State-mandated ratio of 1 school counselor per 450 students, the school

counselors often are not present daily during school operations in rural settings

where the student population is a fraction of the prescribed 1:450. The community’s

implicit expectation is that school counselors should serve as enthusiastic

advocates for GSD students in their schools. However, a national survey of school

counselors reveals that many feel less competent compared to community counselors

when supporting this particular student population (Shi & Doud, 2017). This lack of

confidence in their ability to effectively address the needs of queer students could

result in less engagement with this vulnerable group of adolescents.

The authors have a twofold purpose: 1. Present the research findings on the culture of a rural Montana community and its perceptions of its GSD youths’ needs and 2. Provide an action plan for school counselors in rural areas to better address their perceived lack of readiness to support this population. Over the past year, the research team conducted a participatory community needs assessment in a small, rural community in Montana. Our initial goal was to gain a better understanding of the services residents of this community consider necessary but lacking in their town. What we have discovered over the course of a year should be taken into account when developing various intervention plans for that community. This article records some reseacher observations and an outsider to that community. It provides an ethnography of the culture of a small, rural community – unique in many ways, and similar to other rural towns across Northwestern America.

A Note about Language

The terms "Gender and Sexuality Diverse" (GSD) and "LGBTQ+" are used interchangeably

in this article, with the term "queer" also being utilized. While some individuals

may experience discomfort with this word, it is important to note that Generation

Z has embraced this term, reclaiming it from a troubled past (Jones, 2018). Language

evolves over time, and terminology may differ significantly from region to region.

These shifts can present challenges for individuals seeking to avoid causing offense

and promote inclusivity (Lev, 2013). As of the time of this writing, all the terms

used here are currently in use by the queer community as self-descriptors.

Method

Contemporary knowledge management methodologies (Kane et al., 2006) are based on constructivism, which recognizes that the interpretive nature of language enables us to communicate our observations and experiences without being confined by the concepts of "truth" or "absolute knowledge."

The ethnographic approach is fluid and adaptable, where the researcher takes an emic perspective and studies the phenomena occurring in natural contexts. It is important to note that we chose to orient our inquiry by framing it in the methodology of (1) ethnography grounded in community-based research (CBR), (2) institutional ethnography (IE), and (3) action-oriented ethnography (Reid & Russell, 2017). In CBR the researchers’ interpretation is solely focused on the benefit to and collaboration with the studied community, with the development of trust and communication considered essential for developing the study. The “institutional” focus means the researchers are committed to understanding the broader, systemic contexts within the institution of the school, defining resources and limitations for the community participants. We acknowledge that how individual and collective behaviors appear in the community is engineered by larger systems (resources, barriers, institutions, hierarchies) already embedded in the community. Lastly, the “action-oriented” characteristic means that research involving individuals must have actionable goals.

Ania’s experiences working with and learning from residents of a rural community in Montana have provided valuable insights into community dynamics and the challenges rural populations face. The descriptions of the process around the CBR community needs assessment, the separate study that inspired this ethnography, provide the background and document the researcher’s immersion in the community, though they are secondary to this study.

Participants – the Researcher and the Small Rural Community

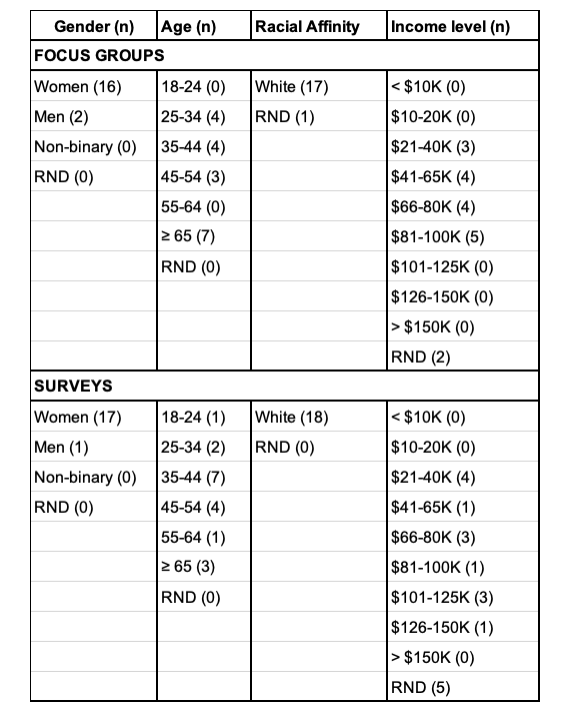

The participants in the community needs assessment – the backdrop for this ethnography

- included residents of the small town where the research team gathered data: 18 adults

who took part in in-person focus groups, and 18 adults who filled out our online survey

(see Figure 1 for demographic analysis of the sample).

*RND - Rather Not Disclose

Figure 1- Demographic Table

The Principal Investigator (PI) conducted an initial phenomenological study and subsequently undertook ethnographic reflection on the interactions among all participants: the researchers, the community consultants, and the community residents, and used storytelling to capture the community's reactions to questions about their perceptions of the needs and resources available locally for GSD youth.

The first author is a middle-aged, white, heterosexual, immigrant cisgender woman. In the context of this study, it's important to note that this author’s commitment to supporting the GSD community, particularly young people, is rooted in her early encounters with injustice and the harm caused by homophobia and exclusion. The first author was the PI on the community assessment and the primary author of the ethnography.

The second author is a middle-aged, white, gay, cisgender American man. He lives in the rural South and has been working as a School Counselor in public schools for over a decade. His commitment to supporting the GSD community as a whole, with an emphasis on queer youth, is a result of his personal and professional experiences.

The authors, Ania and Jeremy, met during a Ph.D. program at Oregon State University and share a dedication to advocacy and service in their respective communities.

Procedure

This study resulted from the reflexive work conducted by the first author, Ania, as part of a Community-Based Research (CBR) community needs assessment in a small rural town in Montana. The process involved several visits to engage residents through focus groups, complemented by an extensive analysis phase with a team of researchers, community consultants, and graduate students. During this project, Ania engaged in reflection on several key areas:

(a) An increasing awareness and appreciation of the community's culture through interaction and observation.

(b) The depth and relevance of the collected data concerning perceptions of gender and sexually diverse (GSD) youth, though not the main focus, proved crucial in understanding local attitudes toward minorities.

(c) Mentoring opportunities for student researchers on the team, enhancing their field skills and understanding of qualitative research methods.

(d) The importance of the researcher's responsibility in accurately and rigorously representing the findings, coupled with the humility to convey them effectively.

While not the community needs assessment’s central focus, exploring community perceptions of GSD youth provided essential insights into the town’s cultural dynamics. Ania's ethnographic exploration developed alongside the community assessment, interpreting participants’ conversations and noting significant non-verbal cues, especially during discussions about the needs of GSD individuals.

The article captures Ania’s understanding of the town’s culture and how its residents perceive the needs of GSD youth derived from immersive and reflective engagement. Jeremy, the second author, contributed his expertise, particularly in reflecting on community support structures for GSD youth in schools, further enriching the study’s analysis.

The procedure outlines the reflective and collaborative approach between Ania and Jeremy, used to explore and document the community's perceptions and conceptualizations of the needs of GSD youth.

IRB Approval

The community needs assessment conducted in a small rural Montana town has received approval from Montana State University's Institutional Review Board (IRB-2023-780). After analyzing the data, detailed reports were presented to the County Commissioners, who oversee managing the county’s budget and legislative matters. These findings were also shared and discussed in a community presentation, ensuring transparency and public involvement.

Similar to the community needs assessment, the ethnographic study conducted alongside this assessment prioritized benefiting the community. The GSD youth are a particularly vulnerable population in this environment, as they face challenges within the small-town culture marked by a lack of understanding and support for them. To further protect the GSD youth and other participants who discussed topics considered "taboo" in their community, we have ensured the community's location remains confidential.

Results

The results are categorized thematically, drawing on phenomenological and ethnographic approaches to provide a concise organization. Throughout this ethnographic reflection, the fundamental principles of the rural community's culture – where the data collection for the qualitative community needs assessment was approved by the Montana State University Internal Review Board – are emphasized. The findings obtained from the ethnography form the basis for a set of recommendations for the best practices of rural school counselors, which are detailed in the Discussion section.

Arriving in rural Montana – the culture of extreme ownership as a background for reflecting on GSD youth needs.

The small town where the community needs assessment project was conducted is situated in a valley surrounded by mountains. Driving over the mountain passes on either side of the valley can be challenging during the winter, and occasionally, the roads are closed, isolating the town and creating a sense of remoteness. This geographical location significantly influenced the culture observed during interviews. The focus on self-sustainability emerged as a fundamental aspect of daily life, as the prolonged and harsh winters necessitate that every resident must be prepared to endure temporary isolation. Additionally, the prevalent perception of living in the valley is that abundant resources attract individuals to this natural haven, offering opportunities for fishing, hunting, and independent living. Additionally, men are often identified as the primary providers for their families. Lastly, the community's conservative values have implications in the current political climate, affecting the acceptability of different forms of diversity.

The concept of "extreme ownership" emerged during one of the discussions with the community consultants who assisted in conducting the community needs assessment. It appeared to encapsulate the ethos of the studied community and its members. Coined by former U.S. Navy SEAL officers Jocko Willink and Leif Babin, "extreme ownership" is a leadership philosophy described in their book, "Extreme Ownership: How U.S. Navy SEALs Lead and Win" (Willink & Babin, 2017). At its core, this philosophy emphasizes that leaders must take full responsibility for every aspect impacting their mission and team and this basic tenet can be communicated in contexts other than military (Pierce et al., 2001, 2003; Silberman et al., 2022). This leadership style, characterized by individual accountability, a focus on the team's success, and a pragmatic vision, seems to naturally embody the spirit of rural communities in America. During the community needs assessment, participants expressed a longing for this type of strong leadership, as well as care and deep concern for their youth, particularly those in the GSD community. I found it touching to hear the intimate self-disclosures made by several participants as they discussed the existing challenges in their community and their aspirations for greater inclusivity. However, it became evident that the responsibility for creating a more inclusive environment was often deferred to the local school to address.

The community showed a range in understanding of the GSD youth’s needs in their area.

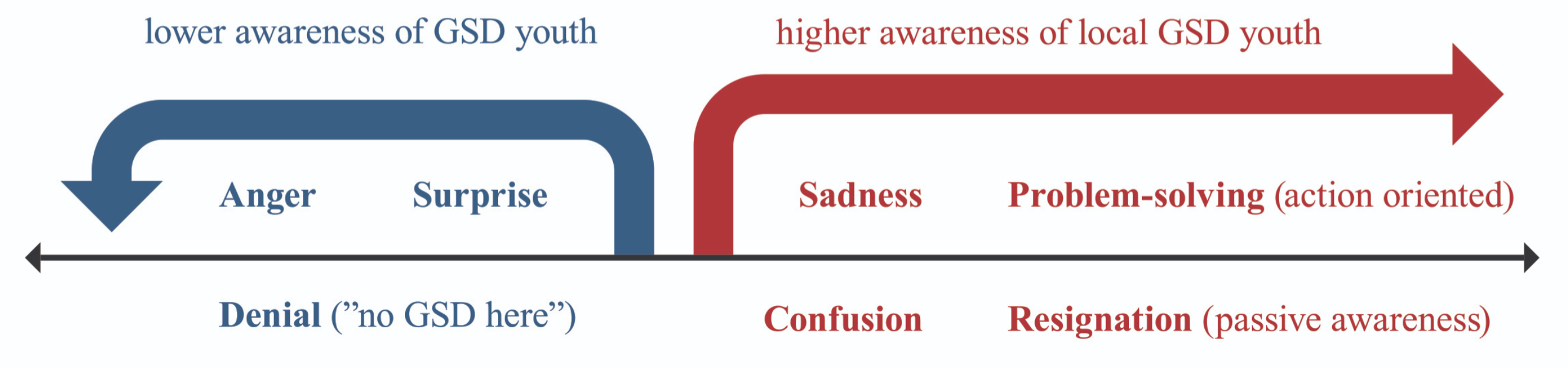

The community’s responses ranged from surprise, confusion, and skepticism regarding the presence of GSD folks in the community to sentiments of sadness and resignation when asked about the needs of this population (Fig.2).

Figure 2 -Emotional Spectrum in Community Reactions to Local GSD Youth Needs

Notably, for those in the mid-range of this spectrum, the main concern and identification of the GSD population was squarely put on children and youth in the community. Participants voiced concerns about the quality of life and access to resources for the GSD youth. When asked about their ideas on the needs of nonbinary folks in their valley, most participants responded with initial confusion, marking that the issue is not something they had considered previously. People who appeared confused or surprised by the question initially often conveyed feelings of sadness and helplessness but then proceeded to engage in brainstorming and problem-solving. Most respondents felt that schools are the best places for GSD youth to receive support. However, they were unsure about how that support could be effectively communicated or provided.

In contrast, one participant, whose views were captured through a separate survey, reacted with anger to the question. Given the limited sample size (18 survey respondents and 18 focus groups participants), I suspect that this single response may reflect the perspectives of other community members whose more conservative values were not well-represented in the focus group discussions.

Due to a lack of resources, there is a strong focus on self-survival, but the community still has some awareness of others' needs, especially GSD youth.

As we conducted focus groups and explored the town, I couldn't help but notice the juxtaposition of coziness and expansiveness within this community. Positioned at the heart of the valley, the town exuded a feeling of unity while extending in all directions towards the mountains, highlighting the delicate balance between togetherness and individuality. While residents spoke of relying on their neighbors for assistance during snowstorms, it was evident that most individuals prioritized taking care of their immediate families before extending their support further. Additionally, our study revealed that the local school played a central role as the primary, if not sole, provider of resources for the GSD youth in the community, with the public library receiving an incidental mention. It became clear that the responsibility of creating a welcoming environment for GSD youth in the town rested heavily on the school and its leadership.

The establishment of a community center has long been a common goal in this community. However, previous attempts at community improvement have faced challenges, with some residents hesitant to prioritize community needs (which means the town's growth) over concerns about the changing social and cultural landscape. Many residents expressed being prepared to deal with limited resources or logistical inconveniences in order to preserve a "small town" spirit. It has become evident that fostering a sense of empowerment within the community is crucial, and the emerging group of citizen-leaders is dedicated to driving change and shaping the future culture of the town.

Discussion

The necessity to be resilient and self-sufficient in the studied community was palpable in all interactions and seemed to be a fact of life - accepted by the community. The concept of extreme ownership(Willink & Babin, 2017) is congruent with the attitudes of residents participating in the study and what we encountered in town – when visiting schools, post offices, stores, and eateries. While some participants expressed a concern for GSD youth, it was believed that the public schools may be the place where these students would find support.

While local school was assumed to carry the most responsibility for addressing GSD youth’s needs, another motif in the focus groups I noticed is that there is a desire for the community center to serve as a safe space for GSD youth, providing them with access to essential services and opportunities to stay connected with their community. Some participants in the focus groups expressed their preference for safe spaces for GSD youth to be situated in a neutral, non-academic environment (outside of school), free from judgment and social labels, in addition to resources in the school setting. Although some residents were aware of this need, others seemed uncertain, possibly due to limited interactions with GSD youth, which hindered their recognition of this population as integral members of the community. In conclusion, there is currently limited awareness among most community members about the needs of the GSD population.

The variety of the responses concerning the nonbinary and GSD population, and specifically GSD rural youth underscores the findings. The range of emotions that were ellicited by discussions about the needs of the local GSD population resonated through all self-disclosures: just as addressing the cultural shifts and rapid growth of the town caused distress for some of the community members, so did acknowledging the diversity of gender and sexuality in the towns’ population was challenging the collective culture. Recognizing the needs of GSD youth as a new responsibility, many participants in focus groups and survey respondents swiftly embraced the cultural principle of extreme ownership (Willink & Babin, 2017), striving to include and support all members of their community.

Implications

This study highlights the perceptions of community members regarding the needs of GSD youth in rural communities. While there is a general concern for rural youth, the specific needs of GSD individuals are often disregarded. These discoveries hold significant implications for school counselors operating in these areas.

First and foremost, school counselors must acknowledge that working in rural communities may entail being the sole reliable source of support for GSD youth, underscoring the importance of their readiness to take on the role of an ally. The ASCA Ethical Standards for School Counselors clearly state that advocating for social justice for queer students is part of the school counselor's role. Despite facing numerous demands on their time and energy, school counselors must not overlook the importance of acknowledging and working towards the well-being of vulnerable groups of students.

In socially conservative rural communities, it is crucial for school counselors to actively engage with the community in order to be effective. While advocacy work may begin in the counselor's office, it is essential for it to extend beyond that space The second author notes that involvement with the community may entail attending school events and supporting families during difficult times. It is important for parents to perceive school counselors as being genuinely invested in the well-being of the community and its members, rather than solely focused on academic performance and attendance. In close-knit communities, being perceived as an "outsider" can pose a challenge for school counselors aiming to engage in advocacy work. The second author posits that by becoming involved with the local community, school counselors are better situated to undertake advocacy work.

School counselors must acknowledge the significant involvement of principals and other administrators in rural communities (Preston & Barnes, 2017). It is crucial to educate school administrators about the needs of GSD students and secure their commitment to the well-being of these students. Without this commitment, efforts such as establishing school-wide nondiscrimination policies or GSD support groups will likely be confined to the counseling office.

Additionally, school counselors should collaborate with administration to assess the teaching staff's knowledge in supporting GSD students in their classrooms. Providing professional development to staff may involve workshops, lectures, and distributing printed materials. Studies show that educators who cultivate inclusive classroom environments by using inclusive teaching materials and addressing homophobic and transphobic language can have a positive impact on their students.(Shelton et al., 2019).

It is important to acknowledge that some teachers may have limited expertise or capacity to effectively undertake these tasks. It is crucial to assess where teachers are in a non-judgmental manner and provide them with the knowledge and skills they need to support queer students within the school building. Moreover, school counselors in socially conservative rural locations should be aware that advocacy work in these areas may progress slowly and may be met with resistance(Meadows & Shain, 2021). Despite this, school counselors are well-equipped to act as catalysts for change. By collaborating with the community, seeking partnerships with the administration, and providing training and support to teachers, it is possible to progress towards a more supportive learning environment - and community - for GSD youth in rural locations.

Limitations and Future Research

One of the primary constraints of ethnographic research is its highly interpretive nature, which is inherently influenced by the individual researcher's perspective. This study is no exception. The insights provided by the researcher, who was immersed in the rural town's culture for a brief yet intense period, represent a snapshot of the town's state at that specific time.

It is conceivable that the limited body of research addressing the community's perspective on the needs of GSD youth to date may render our study and recommendations specific to this particular town. Nevertheless, findings from related research areas suggest that our conclusions are expected to be accurate across similar contexts.

Additional research on the attitudes of the community toward Gender and Sexual Diverse (GSD) populations, especially GSD youth, is essential. As rural America experiences cultural shifts, it is crucial to continue prioritizing support for GSD youth. Conducting more ethnographic research into the changing cultures of rural America will likely result in more sophisticated strategies for engaging communities in prioritizing creating nurturing and inclusive environments for GSD youth.

Future research should investigate the differences among rural areas across the United States. Such studies could unveil localized needs and foster targeted interventions that more precisely address the needs of GSD students. Ultimately, this research aims to inspire improved, more inclusive environments that reinforce diversity and equality in all facets of rural education.

Conclusions

Not all rural communities are identical. This study underscores the diversity among rural communities and the myriad factors that shape the support available to gender and sexually diverse (GSD) students. Variables such as geographic location, political and religious beliefs, socioeconomic status, and demographic composition influence the resources and acceptance levels that GSD students encounter.

The findings provide a valuable framework for rural school counselors, who aim to deepen their understanding of GSD students' unique challenges and develop effective support strategies. Recognizing the non-uniformity among rural settings is vital, as it encourages personalized approaches that respect the nuances of each community.

References

Adelman, M., & Woods, K. (2006). Identification without intervention: Transforming the anti-LGBTQ school climate. Journal of Poverty, 10(2), 5-26.

Baker, K. (2016). Out Back Home: An Exploration of LGBT Identities and Community in Rural Nova Scotia, Canada. In (pp. 25). NYU Press.

De Pedro, K. T., Lynch, R. J., & Esqueda, M. C. (2018). Understanding safety, victimization and school climate among rural lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 15(4), 265-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2018.1472050

Desai, S., & Affrunti, N. (2023). CDC Releases Youth Risk Data Trends. Communique, 51(7), 25-26.

Gray, S. A. O., Sweeney, K. K., Randazzo, R., & Levitt, H. M. (2016). "Am I Doing the Right Thing?": Pathways to Parenting a Gender Variant Child. Family process, 55(1), 123-138. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12128

Jones, E. M. (2018). The kids are queer: The rise of post-millennial American queer identification. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans at risk: Problems and solutions, 1, 205-226.

Kane, H., Ragsdell, G., & Oppenheim, C. (2006). Knowledge management methodologies. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(2), pp141‑152-pp141‑152.

Kann, L. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 67.

Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., & Kull, R. M. (2015). Reflecting Resiliency: Openness About Sexual Orientation and/or Gender Identity and Its Relationship to Well-Being and Educational Outcomes for LGBT Students. American journal of community psychology, 55(1-2), 167-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9642-6

Kuff, R. M., Greytak, E. A., & Kosciw, J. G. (2019). Supporting Safe and Healthy Schools for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Students: A National Survey of School Counselors, Social Workers, and Psychologists. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN).

Lev, A. I. (2013). Transgender emergence: Therapeutic guidelines for working with gender-variant people and their families. Routledge.

Meadows, E. S., & Shain, J. D. (2021). Supporting gender and sexually diverse students in socially conservative school communities.

Oswald, R. F., & Culton, L. S. (2003). Under the Rainbow: Rural Gay Life and Its Relevance for Family Providers. Family relations, 52(1), 72-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00072.x

Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2001). Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Academy of management review, 26(2), 298-310.

Pierce, J. L., Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2003). The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Review of general psychology, 7(1), 84-107.

Preston, J., & Barnes, K. E. (2017). Successful leadership in rural schools: Cultivating collaboration. The Rural Educator, 38(1), 6-15.

Reid, J., & Russell, L. (2017). Perspectives on and from Institutional Ethnography. Emerald Publishing Limited. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/montana/detail.action?docID=4923794

Shelton, S. A., Barnes, M. E., & Flint, M. A. (2019). “You stick up for all kids”:(De) Politicizing the enactment of LGBTQ+ teacher ally work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 82, 14-23.

Shi, Q., & Doud, S. (2017). An examination of school counselors’ competency working with lesbian, gay and bisexual and transgender (LGBT) students. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(1), 2-17.

Silberman, D., Aguinis, H., & Carpenter, R. E. (2022). Using Extreme Pedagogy to Enhance Entrepreneurship Education. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 6(3), 546-560. https://doi.org/10.1177/25151274221144218

Stewart, H., Jameson, J. P., & Curtin, L. (2015). The relationship between stigma and self-reported willingness to use mental health services among rural and urban older adults. Psychological services, 12(2), 141.

Szprengiel, K. (2018). Children Coming Out: The Process of Self-Identification. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Americans at Risk: Problems and Solutions [3 volumes], 17.

The Trevor Project. (2006). Library of Congress. Retrieved 08/01/2024 from https://www.thetrevorproject.org/

Willink, J., & Babin, L. (2017). Extreme ownership: How US Navy SEALs lead and win. St. Martin's Press.