There is so much beauty interwoven with all the hurt: School counselors' decisions to leave rural positions (JSC v20, issue 1, article 2)

Authors: Kirsten Murray, Jayna Mumbauer-Pisano, Timothy Kempff

Correspondence concerning this article can be sent to kirsten.murray@umontana.edu

Abstract

Rural school counselors are a part of unique professional contexts. Rural school counselors often navigate challenges such as isolation, dual roles, and managing a disparity of resources. Benefits of rural practice include strong community identity and cohesion, resourcefulness, and a deep investment in a place and its people (Boulden & Schimmel, 2022; Grimes, et al., 2023). Rural communities continue to face professional shortages, especially in the health and education fields (Ingersol & Tran, 2023; Russell et al., 2021). Recruiting and retaining mental health professionals, including school counselors, is a complex and multifaceted problem resulting in significant health disparities for rural residents (Morales et al., 2020). This research explores the lived experiences of rural school counselors who have left rural schools. Implications for school counselors, rural school districts, and counselor preparation programs are discussed.

Keywords: rural schools, school counseling, counselor retention

There is so much beauty interwoven with all the hurt: School counselors' decisions to leave rural positions

School counselors play a critical role in supporting students' academic achievement, emotional well-being, interpersonal skills, and career goals (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2023). They deliver student-centered school counseling programs in collaboration with students, families, school staff, and community stakeholders (ASCA, 2019). The benefits of access to a school counselor are well-documented. Students with greater access to school counseling are more likely to succeed academically (Parzych et al., 2019), have fewer behavioral challenges (Carey & Dimmitt, 2012; Lapan et al., 2012), demonstrate higher self-efficacy (Bardhoshi et al., 2018) and social skills (Steen et al., 2018), and show greater college and career readiness (Lapan et al., 2019).

Unfortunately, one in five students, or approximately 8 million children, do not have access to a school counselor (The Education Trust, 2019). Rural schools are more likely to lack a school counselor compared to urban schools (Gagnon & Mattingly, 2016). This is especially troubling given the increased barriers to well-being experienced by rural students, where poverty and exposure to adverse childhood experiences are more likely (Ingersoll & Tran, 2023; Russell et al., 2021). In rural areas, school counselors are often the only mental health professionals in their communities, and without them, students often go without mental health support altogether (Crumb et al., 2021). The purpose of this research study is to explore the lived experiences of school counselors who decided to leave their positions in rural schools. Our aim is to give a voice to these school counselors, shedding light on the complexities of rural school counseling and the multifaceted reasons that contribute to their decision to leave.

The Rural Context

Twenty percent of individuals in the United States (US) live in rural areas, defined by the US Census Bureau as areas with low population density and a significant distance from an urban area (2024). Rural areas in the US have many strengths and assets, including higher social cohesion in their willingness to cooperate in order to survive and flourish, (Moss et al., 2023; Stanley, 2003), a strong sense of community identity and pride, and rich cultural traditions that persist across generations (Meit et al., 2018). However, there are also challenges in rural communities that create significant barriers to overall well-being. Rural children have a higher likelihood of exposure to several types of adverse childhood experiences (ACES) including economic hardship, parental separation/divorce, household incarceration, witnessing household or neighborhood violence, having a family member with a mental illness, and household substance misuse (Crouch et al., 2022). Rural children are also more likely than their urban counterparts to experience four or more ACES, making them especially vulnerable to future risky behavior, such as problematic substance use (Crouch et al., 2022). Rural Americans are also at a higher risk for suicide. Over the last two decades, suicide rates have increased 46% in rural areas compared to 27% in metro areas (Garnett et al., 2022).

Despite the increased mental health concerns in rural areas, many individuals who need support lack access to treatment and support options, including school counselors (Ingersol & Tran, 2023; Russel et al., 2021). The National Rural Health Association identifies four key barriers to rural mental healthcare, known as the “Four As”:

- Access to Care: How easily one can access healthcare in their community. Rural residents without personal vehicles may be particularly isolated from care.

- Availability: The presence of mental health care in rural areas. Rural areas are more likely to experience mental health professional shortages compared to urban areas.

- Affordability: The cost associated with mental health care. Low reimbursement rates for services, lack of insurance, and high out-of-pocket expenses make it difficult for rural individuals to afford care.

- Acceptability: The perceptions of mental health services within the community. Factors such as decreased mental health awareness, increased stigma, and the presence of providers who may lack cultural humility can make mental health care feel less acceptable.

Rural School Counseling

School counselors often hold a unique position within rural communities and can oftentimes circumvent these barriers to rural mental healthcare. They are more accessible and available to youth and families due to their presence in schools and the nature of their services being included within public education. School counselors may also improve the acceptability of counseling services (Bright, 2018). Rural youth and families might feel more comfortable speaking to their school counselor than to a private mental health clinician (Grimes et al., 2014) and often serve as a bridge between the school and outside community, connecting students to resources and supports that they may not have otherwise accessed (Bright, 2020). Finally, school counselors in rural areas have a unique vantage point in terms of advocacy and social justice efforts. School counselors who are deeply rooted in their communities and have strong relationships with families can break down barriers and exert influence, despite resistance to change (Grimes et al., 2014).

Despite increasing mental health concerns among youth and the unique benefits of school counseling, schools are currently facing a nationwide school counseling shortage. The Department of Education (2023) reports that 17% of high schools do not have a school counselor. In the state of Montana, the school counselor shortage is even higher. Of Montana’s 826 schools, 23.7% do not have a licensed counselor available. According to Montana’s Critical Quality Educator Report (2023), the number of unfilled counseling positions in Montana schools is thirteen times higher since 2017.

The reasons behind the school counselor shortage are complex and multifaceted. Researchers point to the prevalence of burnout among school counselors as a significant contributing factor (Boulden & Schimmel, 2022; Fye et al., 2020; Mullen & Gutierrez, 2016). Although most of the literature on school counselor burnout focuses on the profession as a whole, the circumstances that often lead to burnout may be more prevalent and severe in rural communities. Researchers have found that time spent on counseling duties (as opposed to non-counseling duties), perceived implementation of the ASCA National Model, and access to quality supervision (whether from a school administrator or a more seasoned school counselor) protect against burnout (Fye et al., 2020). Considering that rural school counselors are more likely to take on non-counseling duties and may lack access to supervision and fellow school counselors for consultation (Goodman-Scott & Boulden, 2020), these findings have important implications in explaining the shortage of rural school counselors.

To date, there is only one study which focuses on rural school counselor attrition. Boulden and Schimmel (2022) explored the factors that impact school counselor retention and attrition in rural settings. Interviews of five participants who have sustained in rural school counseling positions revealed school factors, including sense of support, professional advocacy, multiple roles, and student impact as well as school-community factors including relationships, mental health access, connection with rurality, and state-level school counseling associations that impact both school counselor retention and attrition in rural settings. The authors advocated for smaller caseloads, school counselors’ access to online professional learning communities to ease isolation and loneliness, and counselor educator programs increasing students’ familiarity and experience within rural school counseling as potential means of increasing retention of rural school counselors.

Purpose

Given the demand for school counselors in rural areas and the disparities in mental health care, the frequent turnover of school counselors in rural communities adds more layers to the challenges of available and accessible care, leaving vulnerable children and communities at greater risk. There are few studies that specifically look at retention and attrition among rural school counselors and no existing studies that give a voice to rural school counselors who decide to leave their positions. Unearthing the lived experiences of former rural school counselors, will aid in increased understanding of the complexities of the job, the reasons rural school counselors leave their positions, and increase advocacy efforts within school counseling.

Participants & Methods

Upon institutional review board approval, participants were recruited from alumni lists of the two CACREP accredited school counseling programs in Montana: the University of Montana and Montana State University. Alumni that have served and resigned from rural schools within the last five years were contacted via email and invited to participate. Two focus groups were conducted with six participants. Participants served rural public schools in communities with populations ranging from 200 to 4,573. Participants’ years of experience practicing as a School Counselor ranged from completing their first year of service, through four years of service. Table 1 describes the demographics of the participants.

Table 1. Participant Demographics

|

Participant |

Age |

Gender |

Race |

Marginalized Identity Status |

|

P1 |

25-34 |

Female |

White |

Yes (Indigenous Heritage) |

|

P2 |

25-34 |

Female |

White |

No |

|

P3 |

25-34 |

Female |

White |

LGBTQIA+ |

|

P4 |

25-34 |

Female |

White |

No |

|

P5 |

35-44 |

Female |

White |

No |

|

P6 |

25-34 |

Female |

White |

No |

Focus group interviews were conducted over zoom and lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. Focus group questions included: 1) Tell us about choosing to be a rural school counselor? 2) What was most meaningful about your rural school counseling experience? 3) What barriers did you encounter as a rural school counselor? 4) Describe the deciding factors for leaving your position. Were there any systemic factors that influenced this decision? (ie, the school environment, community politics, relationships with colleagues, etc.) Were there personal reasons that influenced your decision to leave? 5) What would have needed to change for you to stay in the position? 6) What advice would you give to future rural school counselors? 7) What would you change about your training and preparation for rural school counseling? Follow up questions were integrated throughout the focus group process to connect participants via circular questioning and expand the depth and detail of responses.

Author Reflexivity

All authors are affiliated with the University of Montana, JM and KM as professors in the Department of Counseling, and TK as a doctoral student in the same department. JM has been a counselor educator for six years and is currently contracted on a federal grant to expand rural Montana counselor workforce development, as well as supervising counselors-in-training that serve rural communities. She is white, cisgender, queer-identifying and grew up in a suburban setting in the southern United States. KM has been a counselor educator for 17 years and currently serves on multiple federal grants expanding counselor workforce development in rural Montana. She identifies as white, cisgender, heterosexual, and was raised in a rural farming community in the mountain west. She has trained many students serving rural Montana communities. TK is completing his second year as a doctoral student and served as a rural Montana School Counselor for two years. He is also currently contracted on a federal grant expanding counselor workforce development in rural Montana, while also supervising counselors-in-training serving rural Montana in their practicum and internship.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

Recordings of the focus groups were transcribed and coded using van Manen’s (1997) hermeneutic phenomenological framework. Coding and analysis established incidental and essential themes by isolating thematic statements from the transcripts using three approaches to the data: wholistic, selective, and detailed line-by-line approach. Data was further distilled and analysis deepened by attending to linguistic elements in the themes and writing and rewriting interpretations and definitions of the identified themes.

The results were verified using Guba and Lincoln’s (1994) criteria for establishing trustworthiness in qualitative data: credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity. Credibility was established through persistent engagement and trust-building, which included providing detailed informed consent, acknowledging our unique positionality relative to the participants, and addressing the sensitive nature of the study to help participants feel more comfortable with the research process and in sharing their experiences. Dependability was ensured through detailed notetaking and cross-check coding between researchers. Member checks were conducted to verify our results, thereby increasing confirmability. Four participants responded to the final membercheck result procedures, confirming that the findings represented their experiences accurately. Two participants did not respond. Reflexivity was emphasized throughout the research process, as we consistently discussed our backgrounds, biases, and assumptions, and debriefed after both focus groups. Finally, we provide thick descriptions to enable readers to understand the context and nuances of these rural settings, thereby enhancing the transferability of our findings.

Results

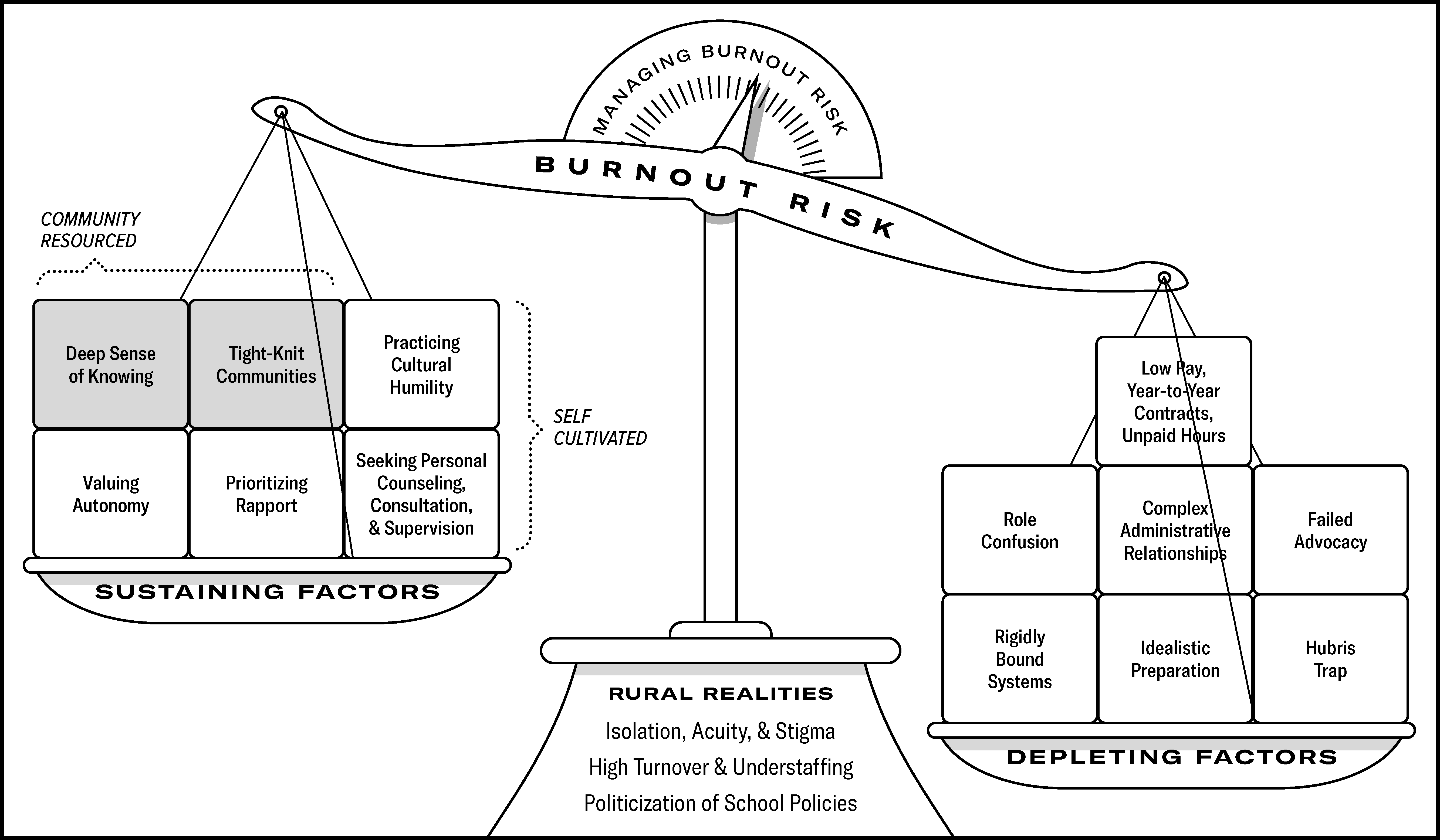

The phenomenology of rural school counselors leaving their positions is represented in the form of a scale, capturing participants efforts to manage burnout risk (see Figure 1). Each portion of the scale represents a major category of the phenomenon: Sustaining Factors, Depleting Factors, Rural Realities, and Burnout Risk. The left side of the scale represents sustaining factors the rural school counselors encountered that brought joy, connection, and meaning to their work. On the right side, we emphasize depleting factors: the experiences, complications, and roadblocks that added difficulty to their already demanding positions. Both sustaining and depleting factors balance on a scale where the base embodies the realities of working in rural environments, factors like scarcity, isolation, and mental health stigma. As the sustaining and depleting factors balance on the realities of rural environments, participants engaged the scale to manage burnout risk. For all six participants, the depleting factors ultimately outweighed what was sustaining, and they found themselves burned out and leaving their positions. What follows is a more in depth look at each of the four categories: rural realities, sustaining factors, depleting factors, and burnout risk.

Figure 1

Rural School Counselors Decisions to Leave

Note. The scale demonstrates the tensions participants experienced as they weighed decisions to leave rural counseling positions. When deciding to leave, participants accounted for sustaining factors, depleting factors, and the rural realities that collectively influenced their experiences of burnout.

Rural Realities

The base of the scale, Rural Challenges, exemplifies the characteristics across participant rural environments that were uniquely challenging because of their rural location. As a result of working in a rural environment, participants noted an increase in isolation, higher acuity of mental health concerns, limited resources, higher turnover of professionals in the school, understaffing, politization of school policy and curriculum, and mental health stigma.

Isolation, Acuity, and Stigma

In many of the rural communities, each participant was the only, or one of very few, mental health professionals. All participants had experiences of being isolated, not only geographically, but professionally. Because rural communities have limited access to mental health professionals, rural places have become deserts of mental health care. When compounded by generations without intervention, today’s school counselors were encountering higher acuity of mental health conditions, trauma, and crisis. In addition to the higher acuity, some rural residents and school employees held mental health stigmas, asserting that mental health conditions were not real, or were seen as a weakness that people could overcome simply by “pulling themselves up by their bootstraps.”

High Turnover and Understaffing

Participants also encountered turnover as a constant in their rural school systems across leadership, counseling, and teaching positions. One participant classified employees into two categories: those that have been with the school system for 20+ years, and those that would stay a few years before moving on to their next position. When exploring the causes that maintained the turnover, participants credited a lack of autonomy, influence, and burnout as a cocktail influencing people’s decision to leave. These turnover rates also compounded the problem of being understaffed. As one participant described entering her position, “when you arrive at a school that is understaffed and under resourced, and everybody is filling multiple roles, like you're going to [fill multiple roles].” When reflecting on the limited resources and high acuity participants were finding in rural places, one participant reflected on the inadequacy of the state endorsed 400:1 ratio of students to school counselors and the lack of resources to support counseling services:

400 kids to one school counselor is a ridiculous number, and I understand why it's there. I'm a very objective person, and I can see both sides to lots of things, but I really wish they would change that number, and I wish it would be based off of more of like a an equation of some sort that they could create, that would look at socioeconomic factors and resources, and just like a bunch of things instead of just a number based off of nothing, because [rural community] is not capable of having one school counselor, even though we only have less than 300 kids. PK through 12. It's just not realistic to ask one person to do that of a PK counselor, that of a middle school counselor, that of a High School counselor and be effective, especially if you want any mental health [services]. All [mental health services] goes out the door. But something has to happen somewhere.

Politization of School Policies

Last, two participants spoke about the recent politization of school policies and curriculum in their rural communities. Two lightning rod issues stood out: social emotional learning (SEL) curriculum and policies for transgender students. One participant described proceeding cautiously when introducing school counseling as an option to parents of students, and how polarizing social emotional learning language had become:

There were some parents who were like, ‘No counseling. No, we don't want this. We don't want our kid anywhere near your room because of social emotional ties and learning’ and just what that [is] associated with.

I’d had a couple of parents pull their students from my lessons for really nonsense reasons, in my opinion.

Another participant described encounters advocating for transgender students in the school system, and finding splits between administration and the student body:

I think of the administrators as being very, um, conservative and, um, and I think the student body is more progressive, and I could definitely see shifts in the way that students like, interacted with one another and like, respected each other's pronouns ……, but with administration, it's almost like they couldn't be bothered to learn how to how to interact with trans students or, yeah, the whole pronoun thing. Like they couldn't wrap their minds around it. And that was really, really tough.

As policies and curriculum continue to become hot-button political issues, rural school counselors were charged with navigating this terrain with respect and thoughtfulness for all students, no matter how divisive. This added an additional layer of thoughtfulness and energy to their already taxed roles and responsibilities.

In sum, the demanding nature of rural environments was described by all participants. Most of these descriptions, however, were offered as realities, and not necessarily deterrents. When coupled with sustaining factors, participants found hope facing these rural realities with inspiration, creative solutions, and teamwork.

Sustaining Factors

Though challenges are encountered regularly in rural communities, all participants spoke to factors unique to rural work that were inspiring and sustaining. The sustaining factors are understood in two subcategories: factors that are resourced from the community, and those that are self-cultivated.

Community Resourced

Deep Sense of Knowing. All participants expressed finding great joy and meaning in their work with rural communities. The rural strengths of knowing your students and their community in a profound way, and the closeness and interdependence of the community set a stage for functioning as a cohesive team. Participants spoke of a deep sense of knowing the students, families, and community members in these rural places. Entering these school systems was not an 8am-5pm compartmentalization but rather stepping into the center of a close community. One participant remarked that “everybody was a lot closer” when comparing her rural to community to more urban counterparts. The participants of this study regarded knowing students as an intimate privilege. They spoke of this closeness as a special, almost sacred thing. The School Counselors were able to greet each student by name and know all students well enough to acknowledge their growth over their years together and know students well enough to understand when something was “off.” They also took pride in helping all students find a sense of belonging, especially when their interests or identities found them on the fringe of their small communities. Their deep commitment to the students provided a sustaining anchor. Here are two examples:

Getting to know the students, I really got to know all the kindergarten through fourth grade students that I worked with. I really loved it. That was one of the challenges about leaving that school was leaving the kids. I also really loved getting to know the families, as I felt like I had more of an opportunity to do that, being in a smaller community.

What I did fall in love with was the intimacy with the students and the staff, and just being able to know every single student.

Tight Knit Communities. Participants acknowledged their tight knit communities as an incredible resource. One participant returned to the community she grew up in with the goal of giving back to the place that invested so much in her, weaving those threads of closeness and commitment to place. For others entering tight knit communities had many advantages:

Rural schools have so much good power in their communities…what a great entry point into a new community, knowing the other teachers, and knowing all the people that are connected to the school. It felt like a really nice way to transition into a new place.

When we did school board meetings, it was such a small community. So, being able to hear from parents and school board and staff on a smaller level of why this was important, or what their concerns were. I do think that that is something that you just can’t get on a bigger level, and I don’t think there’s any way around it. . . . I really think the smaller scale lets you see [the impact] among everyone.

There’s so much beauty that’s interwoven with all that hurt. The hard part [about leaving] is that you meet amazing kids and these amazing people, truly, who want you to invest in their community and want you to stay.

These degrees of closeness and investment positioned the school counselors to function as a part of a team. Several mentioned their relationships with teachers, in particular, remarking on the dedication, support, and partnerships they encountered with teaching staff. One participant regarded the teachers in her school as “One big family. They were all so supportive and so helpful.” These degrees of community helpfulness created a tight-knit and reciprocal relationship for participants where they were also able to support people in ways “they hadn’t gotten in a long time.”

Self-Cultivated

Other sustaining factors were cultivated by the participants themselves. These sustaining factors included: practicing cultural humility, prioritizing rapport with people in their school and community, and seeking out their own counseling, consultation, and supervision.

Practicing Cultural Humility. Participants emphasized entering their communities with cultural humility, being cautious of not entering these places with a savior mentality. Instead, they were sustained in these communities by entering with curiosity and respect. They did not pretend to have all of the answers to their school’s challenges but rather took a learning position to understand the complexities and resources at play. One participant put it like this:

The community I worked in had a lot of their own struggles. There was a lot of poverty. There was a lot of drug use. There was a lot of things that these kids were growing up with. They were still a really close-knit community, and you can’t just bust in and be like, here I am. I’m going to save all of your feelings, and it’s going to be great . . . . . being humble enough to come in softly and respectfully . . . . like not coming in too strong or like being too pushy.

By entering communities with cultural humility, the school counselors became vested in their systems as learners who were invited into the team and eventually held a role as a reliable problem solver. Coming in softly helped them build an interconnected role in the community that became a sustaining factor.

Valuing Autonomy. Several participants valued the autonomy they had in these rural places. They experienced the freedom to build new programming to serve students after communities and schools had experienced a dearth of services. These participants valued the independence of their work as it fostered creativity and an ability to be directly responsive to student needs.

My admin kind of left me alone, and so I could build any program that I wanted to that was beneficial to the students.

I also think the autonomy like just, you know, I obviously had to run everything by my admin, and it was really cool to start new programs and new procedures, like we started a really cool suicide screening assessment.

Prioritizing Rapport. Participants’ cultural humility practice was also closely tied to intentionally building rapport with individual school and community members. Participants noted the value of individual relationships, and investing in them. Here are two examples of how intentionally building rapport was sustaining and helpful for the participants:

Rapport is honestly, like …. you probably will get to know everyone in your school, both students, staff, and parents. And just like any good counseling relationship, rapport is the biggest thing because you're gonna fail. You're gonna make mistakes. You're gonna have conflicts. You're gonna have successes. You're gonna have all the things. And it's gonna look different with every person that you're interacting with. Rapport is what a relationship and counseling is built off of and has saved my bacon in so many situations. And obviously it's not something only you can control, and you can only do your best to build that rapport.

[Know] your resources, like the school secretary. She was a graduate of the school, and she lived in the community her whole life, and she retired this year. She worked as a secretary there for 25 years, and she wasn’t technically a counselor, but she knew things about these kids and their families and their grandparents and siblings that like, I wasn’t going to know in my 1st year, or even in 4 years. And so, I think being able to recognize that.

Seeking Personal Counseling, Consultation, and Supervision. Participants also cultivated sustaining relationships in their own personal counseling, consultation, and supervision. For most participants, they were functioning as the only school counselor in their building or school system, and there were no immediate school counseling mentors on hand. They put the value of these professional relationships like this:

Through personal counseling and, professional supervision. Um, I've been meeting …. and just working with both of those, as sources of support.

When push comes to shove . . . having a supervisor, a consultation group, some sort of mentor there. If you … know other professionals in your field, hopefully, you can bring some of that relationship with you and say, like, my mentor, my supervisor, my consultation group might not be here with me. They might be hundreds of miles away, but I can reach out to them.

Professional counseling relationships became something they sought out to reduce their isolation, work through complex dilemmas, and process the difficulties of their work. These professional connections were sound sources of stability for participants.

Depleting Factors

In contrast to the sustaining factors of rural work, deterrents were present for participants that collectively resulted in burnout. Sometimes the deterrents would arise as a singular critical incident, and other deterrents culminated over time. Or as one participant put it, “death by a thousand cuts.” Depleting factors included: low pay, uncertain contracts, and unpaid hours; role confusion; complex administrative relationships; failed advocacy; rigidly bound systems; idealistic preparation; and the hubris trap.

Low Pay, Year-to-Year Contracts, and Unpaid Hours. As noted earlier, all participants were practicing in rural Montana Schools. Currently, Montana is ranked 51st in the nation in teacher pay (National Education Association, 2024). With this context in mind, some of the participants spoke to difficulty making ends meet. Others spoke about being on a year-to-year contract, as their district did not have stable funding for her school counseling position. When considering the barriers she encountered as rural school counselor, one participant remarked:

Um, I think the number one thing is pay, which I know that's not controllable in these settings. But I had to work a second job on top of the full-time counseling role, and that was really challenging.

In addition, participants remarked on the unpaid hours they spent at home preparing for meetings, researching interventions and curriculum, and establishing lesson plans. These unpaid hours were typically greater in the beginning of participants careers and required a surprising and unexpected amount of energy. In fact, a few participants no longer in school counseling positions described the joy and relief of being paid for their overtime.

Role Confusion. All participants expressed tensions between their counseling and non-counseling duties in rural schools. On the one hand, participants expressed working to be a team player in schools that were short on resources and personnel. This often meant adapting to be a part of unexpected meetings, managing the infinite campus information system, doing scheduling, and coordinating testing. On the other hand, being overextended as a team player resulted in ignoring counseling duties that took away from directly providing services to students. The resulting role confusion in their school persisted in themselves, teachers, staff, and administration. At times, their roles began to look more like school managers than school counselors. In some cases, disciplinarian duties were also expected. Participant’s autonomy in their school counseling role and school counseling programming shrunk, and they became disconnected with their counselor identity. Participants described role confusion like this:

I had a ton of non-counseling duties that I was doing that I wasn’t fully prepared for. And I felt like that took away a lot of the time from the counseling. I really didn’t feel like I could be there for the students as much as I wanted to be.

Sometimes I think they (teachers) viewed me as an admin. I would walk in, and some of the teachers would be like, ‘Please don’t observe my classroom today,’ and I’m like, ‘I’m not observing you, I’m here to work with a kid.’”

We [administrator and school counselor] had really different takes on the school counselor’s role in dress code enforcement. Un, I was asked to kind of be . . . . both administrators had expressed to all staff that I was the go-to person for dress coding students. If teachers didn’t feel comfortable dress coding, just go to [school counselor] and she’ll talk to the student for you. And the male principal would frequently approach me and say, hey, I need you to talk to so-and-so. And it was always either a female student or a trans student. I had a lot of internal struggles with like, I want to be a team player, and like do what is asked of me, but I disagree so wholeheartedly in this. Um. I felt like I was contributing to a culture of body shaming students who are already really vulnerable.

As role confusion persisted, so did the complexity of school counselors’ relationships with their administrators.

Complex Administrative Relationships. Participants spoke of relationships with principals and superintendents as nuanced and difficult. Descriptors across our interviews included administrative relationships that were unresponsive, unclear, unflexible, and bullying. Others found themselves in triangulated relationships between administrators and teachers. And others still, found themselves in self-compromising positions where they overextended themselves to be pleasing until they had sacrificed so much of their voice that their emmeshed relationships with administrators grew unsustainable.

Communication with admin, was a really, really challenging thing for me that I wasn’t really anticipating. I felt stuck between admin having these unspoken expectations of what they thought counseling was, or what they expected of me, and when I didn’t meet that, they kind of got . . . their communication was really um . . . . challenging. They had unspoken expectations that I didn’t know their expectations until they got irritated when I wasn’t doing something. Or they expressed displeasure in things that I thought I was doing really well. I could never quite live up to what they wanted me to be, and I didn’t really know how to reconcile that.

I was being bullied by an administrator . . . . never in my life have I been treated like that as an adult in a professional environment. And so it just kind of felt like the worst-case scenario.

I was pinned between administration and teachers a lot. Um, with their relationships. And I also just didn't know how to continue to navigate that in, like, an unbiased way. Like, it just felt like it was like, you take my side, or you take that side, and you constantly have to be managing that all the time. And that was really hard.

I just felt like I was being steamrolled all the time. I had a good relationship with my administrator, but I felt like I really sacrificed a lot to maintain that relationship, and that was hard for me to know that I was going to continue to deal with that. . . . I felt like my people pleasing side was out really hard to maintain that relationship. But I, I don't want to continue to do that all the time.

As participants reflected on their relationships with school administrators, they expressed a hopefulness for administrative relationships in future positions. They hoped for relationships that pro-actively built strong rapport and prioritized regular communication, not only coming together in times of crisis. They also hoped to have more influence and clarity about their own role and responsibilities in the school system while being a part of a collaborative team. Participants also had a collective desire for administrator humility and support.

I want to work with administrators who listen and like, respond appropriately to people who disagree with them and understand that we’re on the same side. We want the same things, which is like a functioning supportive school environment. Instead of seeing me as some sort of odd adversary who has zero power.

Failed Advocacy. Throughout their training, participants were taught the value of professional advocacy and practiced the skills of analyzing power structures, collecting data, and engaging in problem solving. Despite these skills sets, several participants watched their advocacy efforts fail, be ignored, and go unresolved. When their advocacy efforts failed, more hopelessness about the structure of their positions settled in. Here are a few examples:

After I exhausted every pathway, every advocacy, every crumb of power that I had to change the kind of shitty situation I was in, and to realize I couldn’t change the circumstances of my job.

So we [participant and another district school counselor] presented a lot of the things we found with how we can improve [role] clarity going forward with the administration. And the superintendent was on his phone the whole time. Um, one of the principals wrote down a couple points, but it felt like it just fell on deaf ears. Um, I remember both of us leaving that meeting and just feeling incredibly defeated. And I remember thinking that that was kind of my turning point. I don’t think I’m going to come back next year.

I even reached out to external people for help. And just like, I got no responses from anyone. And yea, I was just super alone. And it was really hard.

Rigidly Bound Systems. In some cases, participants' advocacy efforts failed when they encountered rigidly bound systems. Rigidly bound systems are known not to let new information in, and as a result don’t accept influence and abstain change. Some systems’ rigid boundaries hesitate to let new people in. When counselors attempted to fully join these systems, they were identified as untrustworthy outsiders. In some cases, the resistance to new people resulted in participants feeling targeted, vulnerable, and unsafe. The unlikeliness of accepting new people or new information into rigidly bound systems played out like this for participants:

You have this new group coming in [new professionals: teachers, counselors]. They want to change things. They’re here with updated evidence and data, and they’re like, ‘Yes! Let’s start with this and then go from here.’ But then you have an older generation, who’s, just like, ‘that seems like a lot of work.’ I don’t know how much they really invest in mental health. And it’s like, well, as long as everything seems fine on the surface, let’s not go trying to fix things.

But I think, especially, unfortunately in rural communities, at least where I was, there was still that stigma of like, mental health isn’t real. We don’t talk about our feelings. We just play sports and don’t need to put any money into that side of the school because it’s not important and you know, you can just buck up and deal with it.

I had this kind of duality, knowing they [students and community] needed help and support. And having, like no trust for outsiders, or anybody coming in with anything new. And so it’s weird, because I felt like I was often asked to help. Whether it was teachers or families or students. And then, when I would step into that role, it was like, ‘What are you doing in our business? Get out of here.’ And it was so. That was, that was a challenge.

I won’t say nothing was going to change, but unfortunately not a lot was going to change. Not enough was going to change to keep me there. I just felt like I shouldn’t have to fight this hard to say that feelings matter, students matter. And I just felt like I was working against people.

As participants encountered challenges, including these rigidly bound systems, the idealism of their education also came into focus.

Idealistic Preparation. Participants described their preparation experiences as being too idealistically bound, focusing largely on well-defined school counselor responsibilities and providing minimal acknowledgement to some of the administrative responsibilities school counselors are likely to be a part of in practice. Skills that were often omitted included lesson planning, writing 504 plans, conducting 504 meetings, building schedules, conducting transcript reviews, managing testing, and guiding FAFSA processing. As one participant put it:

To me it became apparent how idealistic the [training] program is which is like beautiful and great, and I was very swept up in it and loved it. But the reality of rural school counseling is like, you’re gonna do schedules. You’re gonna do all these things that we learned very specifically in the program that that’s not what a counselor does and advocate for change. I believe in advocacy, and I think mental health is the focus. But I also think when you arrive at a school that is understaffed and under resourced and everybody is filling multiple roles, you’re going to too. . . . But like, here’s the deal: here’s what you’re advocating for, here’s how you’re moving things. And in the meantime, here’s the skill set to also doing these [non-counseling tasks].

Participants recommended increasing the complexity of their education to explore the pulls of professional role identity, especially when flexibility is necessary in rural environments. They appreciated the idealism and expectation of clear school-based roles and knowledge in some ways. And at the same time, craved more exploration of how to make and manage incremental change in school systems still navigating the role shift from guidance counselor to professional school counselor.

Hubris Trap. Hubris comes from Greek origins, describing a moral flaw of dangerous overconfidence. In Greek tragedies, hubris often led to the downfall of heroes when the Gods would remind them of their mortality. In this research, the hubris trap captures participant experiences of being pulled to ‘do it all’ or ‘be all things to all people’ when there was no one else in the school system or community to turn to. The pride of doing it all became an ethical tension for a few of the participants, and they were pushed beyond their professional bounds.

There was a little bit of hubris and like I can do it all. And I think, having had the experience of building rapport, and having the experience of setting boundaries, of working with the staff, and of working with 4-year-olds-18-year-olds, you are going to be working with every issue that you were told you’ll probably never have to deal with and having little experience. . . . because it is really hard to say no to people, when people need your help.

Maybe the most exhausting was trying to like, fill all of those gaps. And be that piece of sticky duct tape that’s trying to plug the water pouring out.

I have nowhere to send these kids. I have nowhere to send these families. I’m trying to do all the stuff that I know, like ethically is like beyond my competency, but like no one’s doing it. And if I just don’t, that’s also unethical and not something I can handle.

In the end, the culmination of deterrents including the hubris trap, rigidly bound systems, failed advocacy, complex administrative relationships, role confusion, and low pay outweighed the positive encounters of rural school counseling for these participants that eventually resulted in burnout.

Burnout Risk

Burnout was not a far-off concept for participants. Though many definitions of burnout exist, a definition that most aligns with participant experiences was offered by Gentry and Baranowsky (1998): the chronic state of exhaustion that happens when the perception of demands outweighs the perception of resources to manage the demands. Participants were not surprised by the demanding nature of their school counseling positions, what surprised and accelerated their burnout were experiences with a lack of resources to manage their demands.

Participants continuously mentioned being caught in the tension of what they loved about their jobs and the challenges that ultimately tipped their burnout risk into experiences of disengagement, ineffectiveness, and exhaustion. One participant described her encounters with burnout with a metaphor of being on a “horrible hamster wheel,” where her exhaustion and perception of ineffectiveness continued to be fueled in environments that didn’t accept much influence. A number of participants described winter break as a reflective turning point in their decision to leave positions. Many of the participants decided to leave long before sharing their plans to resign. Once the decision to depart had been made, participants were relieved. Their families held relief for them, too. Yet, they also carried grief about the losses acquired in their decision, especially when it came to how the students would be served. Below are their experiences of burnout in their own words:

Yeah, I can grin and bear it for 4 years, because there were great things too. Just, they got outweighed.

And it sucked because the kids cared so much. And they loved me. And I loved them, of course, because that’s what happens. But like I was just lying to them every day. I’m just like ‘Yea, I’m okay,’ or like, ‘Yeah I love it here.’ When truly I was like . . . never in my life have I wanted to like, quit, and run away so bad, and never have I felt like more alone.

I was just super burnt out all the time. Like, my cup was unfillable for a long time. And so, it’s just not a way to live.

I can even pinpoint the time that it really set in. For me, it was coming back from winter break. I was so excited to go to winter break. I was like, oh, it’s a nice little break for all of us and reset. I know winter break can be really challenging for a lot of the kiddos. I knew what to expect- maybe some more behaviors and some dysregulation coming in. But that first week back was just like, I think I did 6 or 7 risk assessments the first week back. So like, I was going home. I was crying. I wasn’t sleeping that much. And then I’d still have to go home, and lesson plan and it just felt like I was irritable and exhausted, and I couldn’t fully be there for those around me . . . . It wasn’t fair to everyone around me. It wasn’t fair to myself. And then I felt like I was going to work, not excited to be there, and I was just exhausted. It had just felt like you show up, I’m here, I’m going through the motions, trying my best. And yea, it just wasn’t fair to anyone.

I just got to a point where it wasn’t good for my mental health, and I was coming home burnt out and cranky, and it wasn’t good for my family. Just because I was turning into someone that I didn’t want to be.

In sum, rural school counselors engaged in managing burnout risk throughout the entirety of their positions. They consciously engaged their communities to cultivate factors that sustained them and brought meaning and joy to their work. They loved many things about rural school counseling. As time went on, participants encountered deterrents that eventually outweighed many of the positive factors, and resources to manage or change these deterrents were sparse. Ultimately, participants chose to prioritize their health and wellbeing and began processes of burnout recovery once they left their rural positions.

Implications for Rural School Counseling

Participants highlighted their deep sense of connection to both their students and the rural communities they served, while also expressing disappointment and frustration when confronted with the rigidity of the school system and entrenched norms that prevented meaningful reform. At the heart of this struggle were the complex and, at times, difficult relationships between rural school counselors and administrators. Participants explained that their professional identity as school counselors, aligned with the ASCA's definition of the role, often clashed with administrators' expectations. Administrators held inaccurate and outdated perceptions of school counseling, frequently viewing counselors as fellow administrators or guidance counselors tasked with covering duties that weren’t being managed elsewhere. This misalignment between rural administrators’ perceptions and the modern role of school counselors highlights the need for continued awareness and advocacy from ASCA. While ASCA has made significant progress in educating stakeholders—including regulatory agencies and legislators—about the importance of school counseling, further advocacy should target administrator preparation programs and national associations for principals and administrators.

As one participant aptly noted, current student-to-counselor ratio standards in many rural districts fail to account for the unique challenges these communities face, including higher rates of poverty, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and mental health concerns. Additionally, rural school counselors are often paid significantly less than their urban counterparts, despite managing heavier responsibilities and having fewer resources. At the state and federal levels, rural school districts must continue advocacy efforts to address the mental health professional shortage in these communities, advocate for higher pay scales that reflect the complexity of working in rural areas, and support programs that promote better work-life balance for school staff. Rural districts could also collaborate to create online professional learning communities (PLCs) for school counselors, providing consultation, mentorship, and reducing the isolation often experienced in rural school counseling roles.

Implications for School Counselor Preparation

In alignment with previous literature on the challenges of rural school counseling (e.g., Boulden & Schimmel, 2022), participants in this study emphasized the profound isolation they experienced in rural communities, with one participant stating, “Never have I felt more alone.” While collaboration and support are often integrated into school counselor preparation programs through cohort models, group learning, supervision, and professional organization involvement, there is a need for more emphasis on preparing students for the isolation they may face as new professionals. Although many participants eventually sought support through consultation groups, individual counseling, and supervision, these steps were often taken only after they had already begun to experience burnout. Counselor education programs could adopt a more proactive approach by encouraging the formation of consultation groups for emerging school counselors before graduation, given the frequent isolation they encounter in their roles and the lack of required supervision post-graduation.

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) has consistently encouraged school counselors to advocate for their roles in schools by demonstrating the responsibilities of a school counselor and the value of a comprehensive school counseling program to stakeholders (2019). However, the participants in this study raised a critical question that remains largely unanswered: “What happens when these advocacy efforts fail?” While participants felt prepared for the challenges of rural school settings and understood strategies for advocating change, they felt lost and discouraged when their efforts did not result in meaningful outcomes. For some, this was the moment they realized they needed to leave their positions. This realization led us, as counselor educators, to consider the personal and professional toll of failed advocacy and how to address it in our training. While we often emphasize to students the importance of advocacy and the various ways they can advocate as school counselors, little attention is given to how counselors can sustain themselves when their advocacy efforts are unsuccessful. While there has been some attention to this topic in counselor education journals (e.g., Mitchell & Binkley, 2021), further research is needed to explore how to infuse sustainable self-advocacy and self-care into our school counselor preparation, especially when preparing students to work in rural communities.

Limitations and Future Research

The most significant limitation of this research is the homogenous sample, consisting solely of white women between the ages of 25 and 44. While this sample does reflect the demographic of individuals who often take school counseling positions in rural Montana schools, a more diverse participant pool could have offered deeper insights into the various factors contributing to rural school counselor burnout and attrition. Future research endeavors focused on the experiences of men, LGBTQ+, and BIPOC rural school counselors may provide a broader understanding of how different identities and experiences intersect with the challenges of working in rural environments.

This study primarily focused on the reasons why school counselors leave their positions in rural schools. Future research exploring the experiences of rural school counselors who remain in their positions throughout their careers could provide valuable insights into the individual, school, and community factors that contribute to their long-term retention. Understanding what allows counselors to sustain their roles in rural environments could help inform strategies to support continued employment and reduce turnover.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2019). The ASCA National Model: A framework for school counseling programs (4th ed.). ASCA.

Bardhoshi, G., Duncan, K., & Erford, B. T. (2018). Factors influencing self-efficacy among school counselors: A path model. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96(1), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12170

Boulden, R., & Schimmel, C. (2022). The role of school counselors in supporting rural student success. Journal of School Counseling, 20(3), 45-67.

Bright, M. (2020). Building bridges: How school counselors support rural communities. Journal of Educational Leadership, 28(4), 98-110.

Carey, J., & Dimmitt, C. (2012). School counseling and student outcomes: Summary of six statewide studies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(4), 412-419. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.tb00258.x

Crouch, E., Probst, J. C., & Radcliff, E. (2022). Adverse childhood experiences among rural youth: Risk factors and outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 334-340. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306679

Crumb, L., Haskins, N., & Brown, A. (2021). School counselors as rural mental health professionals. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 45(1), 14-26. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000159

Fye, H., Miller, T., & Jones, A. (2020). Preventing school counselor burnout: The role of supervision and support. Professional School Counseling, 24(2), 145-160. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20960717

Gagnon, D., & Mattingly, M. (2016). School counselors in rural schools: A growing concern. Journal of Rural Education, 31(2), 35-51. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v31i2.425

Garnett, M. F., Curtin, S. C., & Stone, D. M. (2022). Suicide rates by urbanization level in the United States: Trends from 1999 to 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Vital Statistics Reports, 71(2). https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:112528

Goodman-Scott, E., & Boulden, R. (2020). Addressing school counselor shortages in rural areas: A policy perspective. American School Counseling Journal, 26(3), 87-104. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20960716

Grimes, P., Smith, L., & Johnson, M. (2014). School counselors as liaisons: Supporting rural students and families. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 29(1), 120-134.

Grimes, P., Smith, L., & Lee, A. (2023). Understanding counselor burnout: Impacts and interventions. Counseling Today, 18(2), 150-165.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K.

Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105-117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ingersol, R., & Tran, H. (2023). Rural professional shortages in health and education fields. Journal of Rural Health, 45(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12583

Lapan, R., Gysbers, N. C., & Sun, Y. (2012). The impact of more fully implemented school counseling programs on the school climate and student success. Professional School Counseling, 16(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0001600105

Lapan, R. T., Whitcomb, S. A., & Aleman, N. M. (2019). College and career readiness counseling support programs. Career Development Quarterly, 67(4), 278-291. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12204

Meit, M., Knudson, A., & Gilbert, T. (2018). Rural health in America: Challenges and cultural resilience. Rural Health Research Journal, 32(4), 17-31.

Montana Office of Public Instruction. (2023). Critical Quality Educator Shortage Report. Retrieved from https://bpe.mt.gov/_docs/Critical-Quality-Educator--Report-Jan-2023.pdf

Morales, A., Bennett, T., & Carter, E. (2020). Recruiting and retaining mental health professionals in rural areas. Journal of Counseling and Development, 98(4), 329-341. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12323

Moss, J., Black, A., & Harper, L. (2023). Social cohesion in rural American communities: Strengths and challenges. Journal of Rural Sociology, 67(3), 123-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12367

Mullen, P. R., & Gutierrez, D. (2016). Burnout among school counselors: A systemic review. Journal of School Counseling, 14(1), 25-40.

Parzych, J., Donohue, P., & Gaesser, A. (2019). The impact of school counselor ratios on academic success. Professional School Counseling, 22(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X19870721

Russell, P., Smith, J., & Lee, K. (2021). Addressing mental health disparities in rural communities. American Journal of Public Health, 111(6), 987-996. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306015

Stanley, D. (2003). Social cohesion and rural community development. Rural Sociology, 68(1), 55-70.

Steen, S., Liu, X., & Shi, Q. (2018). The effects of comprehensive school counseling programs on the social skills of students. Professional School Counseling, 21(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X18778705

The Education Trust. (2019). School counselors matter: The need for more school counselors in American schools. The Education Trust.

U.S. Department of Education. (2023). Nationwide school counselor shortage. Retrieved from

van Manen, M. (1997). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive

pedagogy (2nd ed.). Althouse Press.